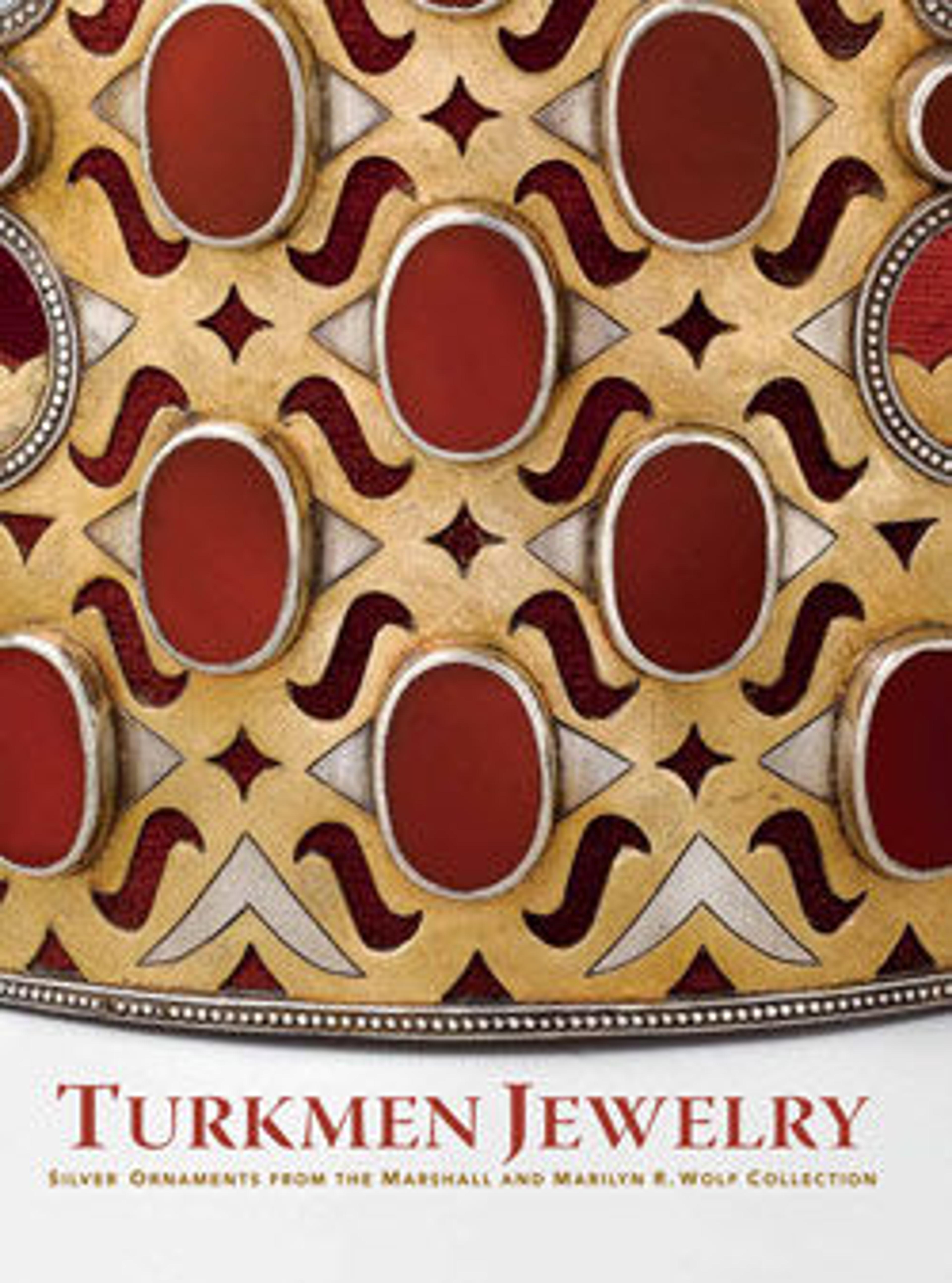

Pectoral Ornament

Turkman jewelry is worn because of its protective powers, and its design is not merely guided by aesthetic preference but has specific references in a set of beliefs that predate the conversion of the Turkman tribes to Islam. This ornament is attributed to the Tekke tribe that once inhabited the Achal oasis in the southern part of present-day Turkmenistan, close to the northern border of Iran. While much of the jewelry made by the Turkman tribes combines silver, gilded silver, and carnelians, Tekke pieces are instantly recognizable from the gilded scrolling patterns covering much of their surface and the openwork scrolls used on many, but not all, pieces. The pair of confronted birds that form the main motif of this object is unusual, however. Although birds are commonly used in the jewelry of other Islamic cultures, a parallel for this piece in Tekke jewelry is nearly impossible to find. The form is also unusual. While the piece is similar to a headdress element, its overall size and proportion of height to width suggest that this was a pectoral ornament, probably worn strung together with several other ornaments that covered most of the chest.

Artwork Details

- Title: Pectoral Ornament

- Date: late 19th–early 20th century

- Geography: Attributed to Central Asia or Iran

- Medium: Silver; fire-gilded and chased, with openwork and table-cut and slightly domed and cabochon carnelians

- Dimensions: H. 4 3/4 in. (12.1 cm)

W. 4 in. (10.2 cm) - Classification: Jewelry

- Credit Line: Gift of Marshall and Marilyn R. Wolf, 2008

- Object Number: 2008.579.3

- Curatorial Department: Islamic Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.