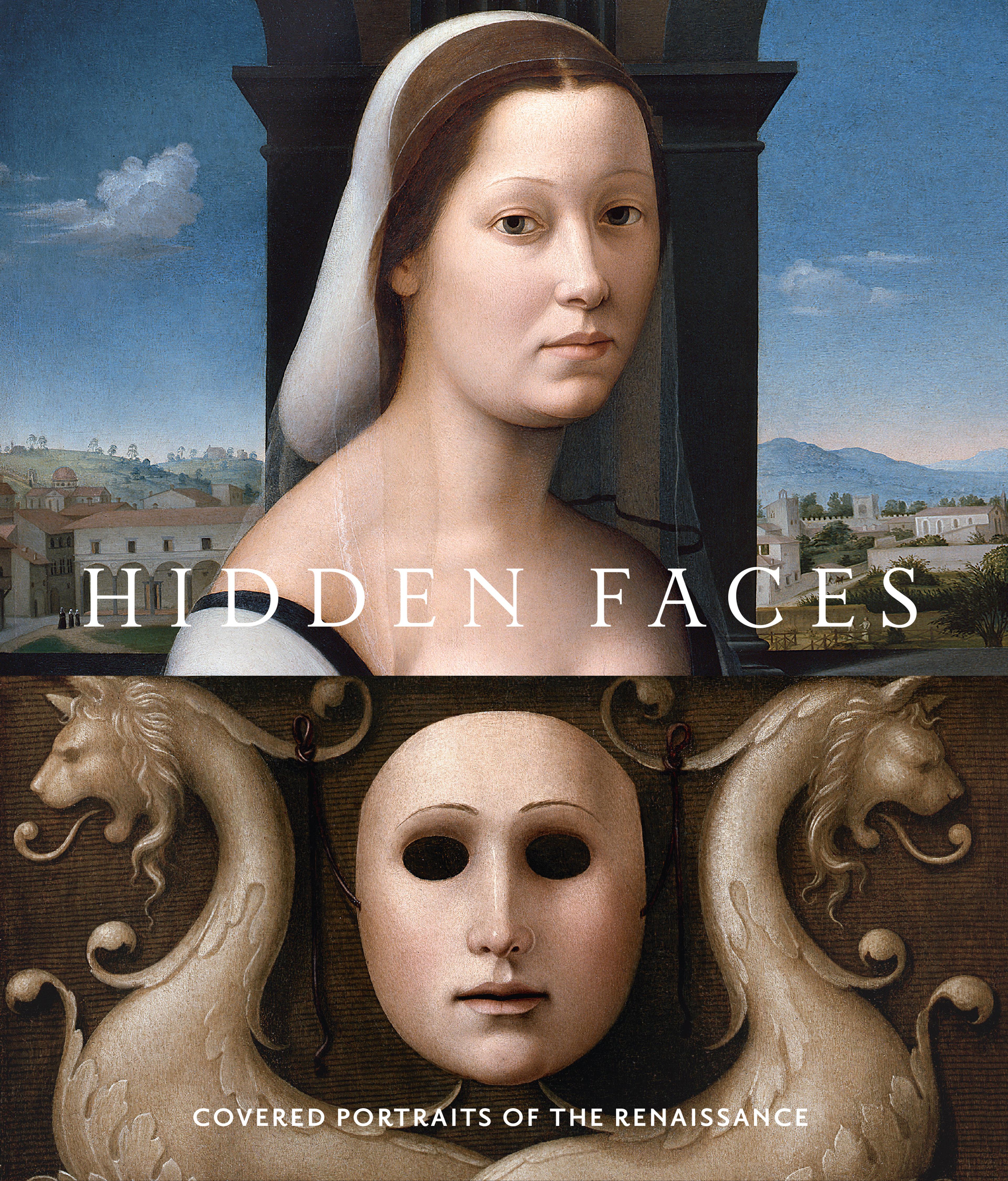

Portrait of a Woman, Possibly a Nun of San Secondo; (verso) Scene in Grisaille

This exquisite and enigmatic portrait and its pendant (1975.1.86) are most likely the works by the Venetian painter and illuminator Jacometto, recorded by the connoisseur Marcantonio Michiel in the collection of a Venetian patrician in 1543. Michiel, who praised them as "a most perfect work," identified the man as Alvise Contarini and the woman as a "nun of San Secondo" (a Benedictine convent in Venice). The paired portraits and the allusion to fidelity on the verso of the male effigy (a roebuck chained beneath the Greek word AIEI, meaning “forever”) would normally suggest a married couple; however, her possible status as a nun makes it difficult to determine their relationship. If the garment is a habit, which seems doubtful given her bare shoulders, she may have led a secular life as a nun or entered the convent as a widow. The portrait may have been commissioned platonically (such cases are known). Alternatively, the wimple-like headdress may represent an entirely secular and contemporary fashion trend. Perhaps the portraits, which probably fit together in a boxlike frame, were designed to hide their clandestine relationship.

Illustrating the influence of Netherlandish painting on Venetian portraiture, the portraits are striking for their meticulous detail, highly refined technique, and luminous, atmospheric landscape backgrounds.

Illustrating the influence of Netherlandish painting on Venetian portraiture, the portraits are striking for their meticulous detail, highly refined technique, and luminous, atmospheric landscape backgrounds.

Artwork Details

- Title: Portrait of a Woman, Possibly a Nun of San Secondo; (verso) Scene in Grisaille

- Artist: Jacometto (Jacometto Veneziano) (Italian, active Venice by ca. 1472–died before 1498)

- Date: ca. 1485–95

- Medium: Oil on wood; (verso: oil and gold on wood)

- Dimensions: Overall 4 x 2 7/8 in. (10.2 x 7.3 cm); recto and verso, painted surface 3 3/4 x 2 1/2 in. (9.5 x 6.4 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Robert Lehman Collection, 1975

- Object Number: 1975.1.85

- Curatorial Department: The Robert Lehman Collection

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.