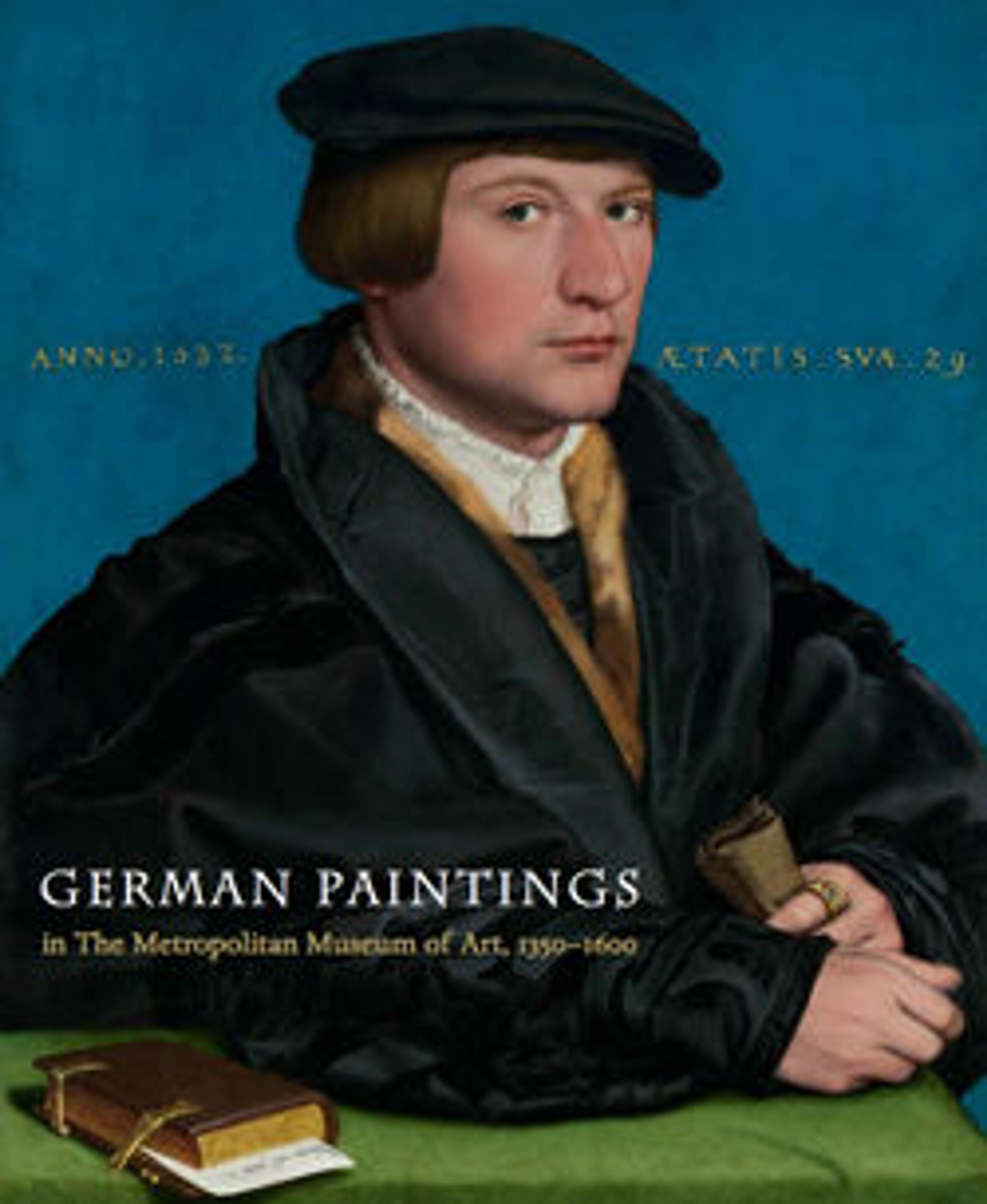

Virgin and Child

This painting testifies to the widespread influence of early Netherlandish masters on German artists of the last half of the fifteenth century. Although the exact prototype for this Virgin and Child is unknown, the composition and figure style can be generally associated with models by Dieric Bouts that were widely circulated through drawings. Technical examination revealed that the underdrawing of the figures was transferred onto the panel from a preexisting pattern. The landscape, however, was painted freehand and bears a close resemblance to a German watercolor drawing (Universitätsbibliothek Erlangen), supporting the attribution to the workshop or circle of Hans Traut.

Artwork Details

- Title: Virgin and Child

- Artist: Workshop or Circle of Hans Traut (German, ca. 1500)

- Medium: Oil, gold, and silver on linden

- Dimensions: 15 5/8 x 12 1/8 in. (39.7 x 30.8 cm)

- Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Purchase, Joseph Pulitzer Bequest, 1922

- Object Number: 22.96

- Curatorial Department: European Paintings

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.