Chroma: Ancient Sculpture in Color

Chroma

Introduction

Contrary to popular belief, most sculptures in the ancient Mediterranean world were colorful. Paint, gilding, and inlaid materials animated and enlivened marble, bronze, and terracotta figures. Over time, much of that polychromy—the term derives from the Greek for “many colors”—has disappeared, leaving representations of humans, animals, and mythical subjects without their original definition and ornamentation.

Chroma highlights ancient polychromy on works of art in The Met collection and reveals new discoveries of surviving color identified through cutting-edge scientific analyses and in-depth research by the Museum’s curatorial, conservation, scientific research, and imaging staff. The exhibition features a series of striking color reconstructions of major sculptures—created by Vinzenz Brinkmann, Head of the Department of Antiquity at the Liebieghaus Sculpture Collection in Frankfurt am Main, and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann—that convey the brilliance and scope of ancient polychromy. Juxtaposed with original Greek and Roman works depicting similar subjects, the reconstructions are based on the results of advanced photographic and spectroscopic techniques and comparative research of ancient works of art. Also unveiled here is a new reconstruction of an Archaic Greek sculpture of a sphinx in The Met collection, completed by the Liebieghaus team in collaboration with The Met.

This presentation provides a window onto multiple aspects of color on ancient sculpture: the practices and materials used by artists long ago; our methods for identifying and re-creating original polychromy today; the critical role color plays in conveying meaning; and the various ways that people have viewed and understood Greek and Roman polychromy over the centuries.

Reconstructions of Ancient Sculpture

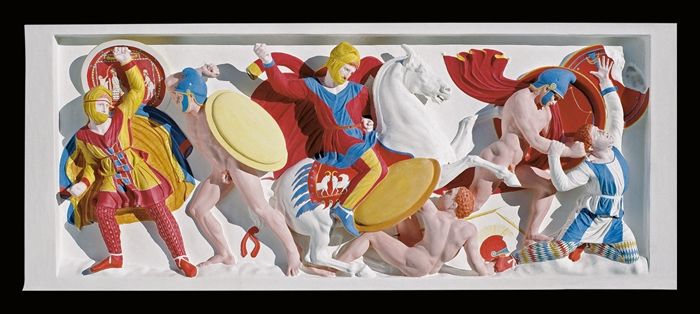

The seventeen color reconstructions in this exhibition represent the work of Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann, leaders in the field of ancient polychromy studies. The Brinkmanns’ reconstructions reflect not only the rigorous scientific, art historical, and archaeological research they have undertaken over the course of more than forty years, but also the contributions of an international, interdisciplinary network of researchers and supporters that has come together over the past two decades. Their work involves a wide array of established and innovative techniques of material analysis—from multispectral photography to X-ray diffraction—and the development of new scientific methods, such as ultraviolet-visible absorption spectroscopy and thermography applied to metal sculpture.

Equally important to the project has been the art historical analysis of ancient imagery and pictorial elements as they appear, for example, in painting. A deep understanding of image types, which were often highly standardized, has been integrated into the reconstructions. The demanding process of physical reconstruction forces the examination of the originals in their totality. This challenging and rewarding practice has in turn provided new insights into historical painting materials and techniques.

Selected Artworks

View allCycladic Sculpture in Color

The harmonious forms of prehistoric marble sculptures made over four millennia ago in the Cyclades islands have inspired modern European sculptors from Constantin Brancusi to Pablo Picasso. A pioneering study of The Met’s Cycladic collection undertaken in the 1990s showed that nearly every example has traces of pigment. Little remains today of the paint that originally adorned these figures. Yet close examination sometimes reveals “ghost” images—where painted areas have weathered differently—or vestiges of pigment. Cinnabar was used for red, azurite for blue, and a green, probably made from malachite, has also been identified (although not on the sculptures in this collection).

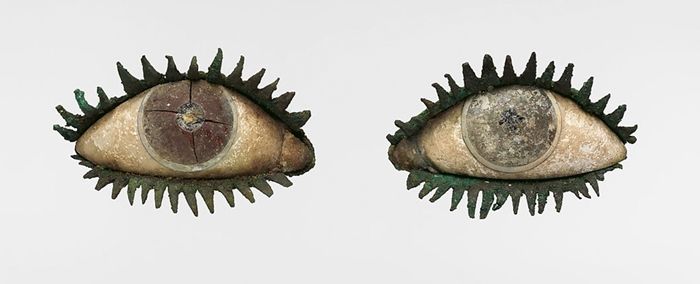

As the reconstruction displayed nearby demonstrates, the effect of the sculptures with their original decoration in color would have been dramatically different from what we see today. Painted elements included jewelry and other adornments, facial features, and hair. The emphasis on the eyes, often portrayed as open and sometimes located in unusual places, activates the figures and suggests that they had a significance and ritual use beyond their burial in tombs.

Selected Artworks

View allArchaic Greek Sculpture in Color

The polychromy of ancient Greek sculpture has been studied for over a century at The Met. Edward Robinson, a Classical scholar and the Museum’s third director (1910–31), wrote an influential article on the subject in 1892. He encouraged the acquisition of sculptures that still bore paint traces, giving visitors some insight into their original appearance. Renowned curator Gisela M. A. Richter made significant contributions to the field through careful analyses of many works in the collection. A watercolor illustration from her article “Polychromy in Greek Sculpture” (1944) presents a color restoration of the Museum’s sphinx based on visual examination. With the enhancement of the conservation and scientific research facilities at the Museum, especially since the 1970s, and the identification of materials used for pigments in Greek art (both naturally occurring minerals and early synthetic pigments such as Egyptian blue), new techniques enabled more sophisticated examination of paint traces. The findings have contributed to our knowledge of the pigments, the nature of the applied decoration on Archaic Greek sculpture, and the methods of the painters.

Selected Artworks

View allClassical Sculpture in Color

Greek art of the Classical period moves away from fixed formulas and toward sensory impressions that correspond to real life (mimesis). Color, with its illusionistic potential, plays an important role in painting and sculpture.

To show figures in dynamic poses, sculptors increasingly worked in bronze, enlivening their creations with applied colors. Scientific research and ancient written sources show that colorful effects were achieved via multiple methods, including the use of different alloys during casting; artificial patination with sulfurous substances; and the addition of bitumen lacquer, other metals (including gold, silver, copper, tin, and lead), and precious stones. The naturalistic effect of these sculptures was apparently so strong in ancient times that many visitors to the sanctuaries believed them to be alive.

The Brinkmanns’ research suggests that the bronze warriors reconstructed here are mentioned in ancient literature (Pausanias 1.27.4) and originally stood on the Athenian Acropolis, where they depicted an episode in the founding myth of Athens: the Athenian king Erechtheus (identifed as Riace A), foster son of the goddess Athena, and the Thracian king Eumolpos (identified as Riace B), son of the sea god Poseidon, look into each other’s eyes shortly before their deadly fight. The death of both opponents saved Athens from destruction.

Selected Artworks

View allColor and Expression in Hellenistic Art

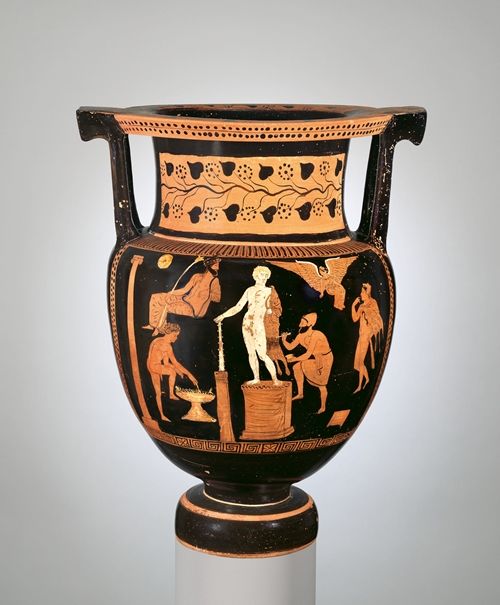

Color intensified the new expressions of movement and emotion in Hellenistic art. The variety of materials used to paint sculpture and other objects expanded in this period. Bright pastels and a more extensive use of gilding supplement the palette of rich earth tones, bright reds, and deep and brilliant blues seen in earlier Greek painting.

Hellenistic art is remarkably diverse in subject matter and style. Color activated the artistic forms and delineated traits that signal identity, status, and prestige. In scenes painted on ceramic vessels and limestone funerary monuments, color articulates the subjects and their actions. It also distinguishes attributes such as jewelry, armor, and drapery types. The liberal application of bright new hues—both as backgrounds and blended with other colors—is a hallmark of polychromy in this period.

Selected Artworks

View allColor and Marble in Roman Sculpture

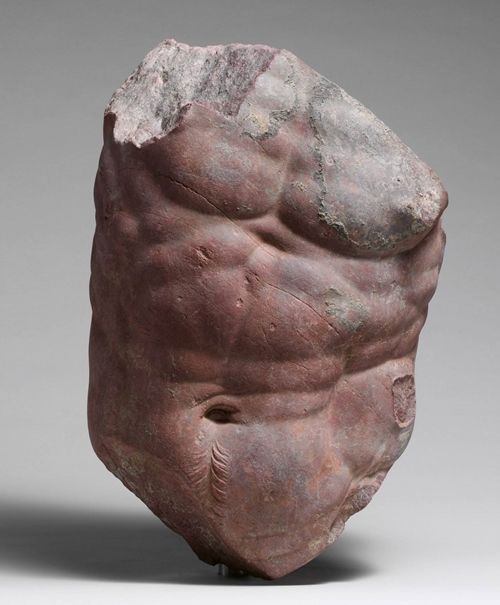

Polychrome terracotta and limestone statues have a long tradition in Italo-Etruscan art, but marble fit for sculpture was not widely available in Italy until the early Roman Imperial period in the late first century B.C. Painted marble works from other places were introduced to Italy with Rome’s conquests of the eastern Mediterranean in the second and first centuries B.C.

Roman patrons began to collect these vividly colored Greek antiques (as we would characterize them today) and commissioned new marble artworks that drew from a range of past Greek styles—albeit fashioned for Roman tastes. Popular subjects like the striding goddess Artemis, which incorporates aspects of Archaic Greek art from centuries earlier, were widely replicated for the Roman art market.

Surviving examples show that replicas of a given type were painted in different ways, suggesting that choices were made individually by the painter or patron commissioning the sculpture. The Artemis from Pompeii, for example—reproduced here in a color reconstruction—is one of at least four. While it was painted in a bright pastel palette, other replicas show the patterns rendered in different colors.

Selected Artworks

View allWhite Marble and Roman Portraiture

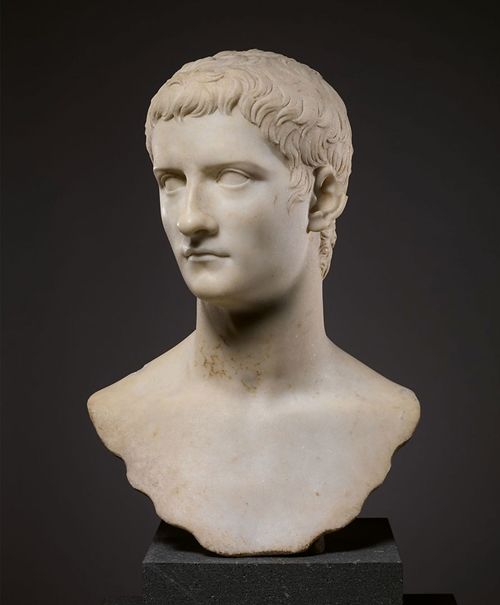

Roman artists combined the properties of white marble—its brilliance and density, permitting a high polish—with applied color to achieve naturalistic effects in portraiture. Color imbued representations of Roman people with lifelike qualities, differentiating individuals and reflecting the context of display in public, private, or funerary settings.

With the absence of color, ancient sculpture loses its original animation and full range of meaning. In portraiture, hair color, flesh tone, adornment, and attributes all become less perceptible. Over time, the monochromatic appearance of Classical sculpture has led to misconceptions regarding the vibrant nature of ancient Greek and Roman art.

Selected Artworks

View allAncient Polychromy at The Met

The Met has a long tradition of scholarship in the field of polychromy. Edward Robinson, a Classicist by training and the Museum’s third director (1920–31), was deeply interested in the subject as early as the 1890s, when he encountered lively academic debates in Europe regarding the existence and extent of applied color on ancient sculpture and architecture. During Robinson’s tenure, The Met acquired many Greek sculptures with surviving color, including several featured in this exhibition.

Equally far-reaching was the work of Gisela M. A. Richter (1882–1972), an internationally esteemed curator of Greek and Roman art. She studied and published extensively on color in Greek artworks, including the Archaic sphinx that crowned the grave marker of a young Athenian—now on view in Gallery 154 alongside a new color reconstruction.

As demonstrated throughout the exhibition, the Museum’s current curatorial, scientific research, and conservation staff remain actively engaged in investigating and presenting manifestations of ancient color.

Selected Artworks

View allThe Brinkmanns’ Team and the Liebieghaus

For more than forty years, archaeologists Vinzenz Brinkmann and Ulrike Koch-Brinkmann have investigated the presence of color on ancient sculpture. Their research integrates photographic methods, scientific analyses, and in-depth art historical study in order to interpret and re-create polychromy in full-size reconstructions of original Greek and Roman artworks. Over time, the materials used in their work have evolved, from original and artificial marbles to plaster and polymers. Recent reconstructions are 3-D printed in crystalline acrylic glass (polymethyl methacrylate), covered with thin marble plaster, and painted in tempera (by Koch-Brinkmann) with traditional pigments and historically accurate binders.

Presented in more than twenty museum exhibitions since 2003, the reconstructions have advanced the understanding and acceptance of color and pattern on ancient sculpture and have significantly corrected misconceptions of Greek and Roman art as monochrome.