The Artist: The master derives his name from two altarpieces commissioned for Frankfurt-based patrons. Active in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, the painter’s origins and training remain unknown. However, stylistic connections between the Frankfurt altarpieces and two other paintings related to Antwerp institutions indicate that he worked in that city for part of his career. Inscriptions on these Antwerp-linked pictures provide useful information about the artist’s dates. One of the frames states that the artist was thirty-six in 1496, suggesting he was born around 1460. The Master of Frankfurt’s

oeuvre reveals the influence of his fifteenth-century predecessors (Hugo van der Goes, Rogier van der Weyden and the Master of Flémalle) as well as the tendency to adapt compositions of his Antwerp contemporaries. With the help of a prolific workshop, the master produced many paintings for sale on the open market. The identification of the Master of Frankfurt with the documented Antwerp painter Hendrik van Wueluwe has gained some acceptance, although no signed works are extant.[1]

The Painting: Surrounded by a group of worshipful angels and his kneeling mother, the naked Christ Child lies in a makeshift manger, gazing up at the Virgin. Standing just behind Mary and holding a single lit candle is Joseph, whose somewhat ambivalent gesture redirects the viewer’s attention back to the central scene. Two other figures lean into the ramshackle dwelling in which the narrative unfolds: one – a piper – holds a hand to his head in awe while the other leans against a column. Five angels float in the air, three of them singing music written on a banner, while in the distance, seen through two arched windows, another angel announces the birth of the savior to the shepherds.

The subject of the Adoration of the Christ Child was popular during the early sixteenth century with many variants on the theme produced for the open market. Many of such scenes were influenced by the account of Saint Bridget of Sweden (ca. 1303 – 1373), who, while on a pilgrimage to Bethlehem, received a vision, which she recounted with certain significant details that relate to the Lehman picture as well as to a painting of the same subject in the Linksy collection (

1982.60.22). Saint Bridget describes a young Mary with long, shining hair, delivering, in an instant, the naked Christ who radiated a divine light that outshone the candle of Saint Joseph. Her vision emphasizes the Virgin’s immediate veneration of her newborn son, accompanied by angels’ sweet singing.[2]

The painter of the Lehman picture included many details from Saint Bridget’s revelation. Significantly, however, he omitted the Christ Child’s radiance, yet retained Saint Joseph’s no-longer-surpassed candle. He also rendered the scene under a sky, which appears as bright daylight in the background, but is darker directly over the protagonists.[3] The night setting of the Linksy picture, on the other hand, provides a dramatic contrast to the light of Christ, creating a vivid focal point for the composition. Both paintings have been linked to a lost night

Nativity by Jan Joest of Kalkar (Netherlandish, active ca. 1515), which itself was indebted to another lost work by Hugo van der Goes.[4] Variations on the general model, produced in the circle of Jan Joest and the Master of Frankfurt, present the scene both in daylight and at night, reflecting the general popularity of the subject in the early sixteenth century and the flexibility with which painters treated Saint Bridget’s account. As noted by Ainsworth, the Lehman picture does not include any evidence of adaptations made to suit a patron’s wishes, emphasizing the likelihood that Antwerp’s open market was the intended destination for this standalone devotional work.[5]

Attribution and Date: Max J. Friedländer attributed the

Adoration to the Master of Frankfurt in 1934, just four years after Robert Lehman purchased it from Bottenwieser. Since then, the picture’s connection to the master has become more tenuous: most art historians place it in the master’s workshop.[6] In support of such an attribution, Wolff highlighted the compositional connection between the Lehman painting and a work ascribed to the Master of Frankfurt (Musée des Beaux-Arts, Valenciennes).[7] Another compelling link to the Master of Frankfurt’s studio is the reuse of the brocade pattern identified by Stephen Goddard in other works attributed to the Master of Frankfurt and his workshop.[8] The repetition of brocade patterns expedited the painting process, and their use in multiple versions of the same composition by the Master of Frankfurt’s atelier seems to reflect increased consumer demand.[9]

Closer to the Lehman picture are two examples of Night Nativities,[10] which more precisely replicate the composition of the Lehman painting, albeit with the more impactful lighting effects.[11] The Lehman painting takes its place among other early sixteenth-century versions of the Night Nativity, created in the ambient of Jan Joest and the Master of Frankfurt and intended for sale on spec.

Nenagh Hathaway, 2019

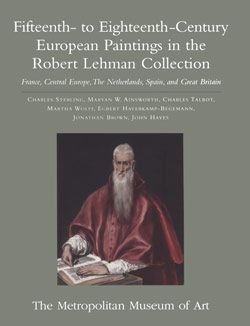

[1] Adapted from Martha Wolff. See Refs., Wolff, 1998, p. 96.

[2] Hendrik Cornell,

The Iconography of the Nativity of Christ, Uppsala, Sweden, 1924, pp. 11-13.

[3] Wolff (Refs., 1998, p. 98) characterized the setting as ‘even daylight’, a description that ignores the gradation towards a deeper blue at the top of the panel. Ainsworth (Refs., 1998, p.246) also describes the scene as ‘an evenly lit daytime event’, highlighting the impact of the change in setting on the ‘sense of mystery’ present in the nocturnal depictions.

[4] Winkler, in agreement with Baldass (1920-21), proposed that Hugo van der Goes initiated the nocturnal Nativity prototype. See Refs., Winkler, 1964, p. 141-145. Friedländer proposed that Jan Joest originated the particular night Nativity variant seen in the Lehman picture, a suggestion supported by Wolff. See Refs., Wolff, 1998, p. 98.

[5] See Refs., Ainsworth, 1998, p. 246.

[6] Wolff rightly dismissed Goddard’s proposal (1984) that the Lehman picture is attributable to the so-called Watervliet Painter. See Refs., Wolff, 1998, 98.

[7] According to Wolff, whereas the Valenciennes picture reflects the style of the Frankfurt master, the Lehman painting is missing "evidence of the master’s personal involvement, his habitual effort, awkward though it may be, to give figures volume and psychological intensity". See Refs., Wolff, 1998, pp. 98-99.

[8] See Refs., Goddard, 1985, pp. 409, 416.

[9] Ainsworth (Refs., Ainsworth, 1998, p. 244) identified at least ten paintings, including the Lehman and Linsky examples, and two drawings, that echo the basic composition of the scene.

[10] For illustrations of these paintings see https://rkd.nl/en/explore/images/62153 and http://collection.dunedin.art.museum/search.do?view=detail&page=1&id=27651&db=object

[11] Both were previously attributed to Jan Joest and are attributed to northern Netherlandish painters by Wolff-Thomsen (1997), who also disagrees with the notion that Joest came up with composition in the first place. See fig. 128, p. 357 and fig. 134, p. 361. Refs., Wolff-Thomsen, 1997, pp. 354-363.

References:Friedrich Winkler.

Die altniederländische Malerei. Berlin, 1924, pp. 151-53, ill.

Max J. Friedländer.

Die altniederländische Malerei. 14 vols. Berlin and Leiden, 1924-1937, vol. 9 (1934), pp. 17-18, 126, no. 4d.

Wilhelm R. Valentiner. "Jan de Vos, the Master of Frankfort."

Art Quarterly 8 (1945): p. 212, fig. 6.

Friedrich Winkler.

Das Werk des Hugo van der Goes. Berlin, 1964, p. 153, fig. 115.

Max J. Friedländer et al.

Early Netherlandish Painting. New York, 1967-1976, vol. 6a 7? (1971), p. 85, add. 204, pl. 131; vol. 9a (1972), pp. 15, 52, 133, n. 24, no. 4d.

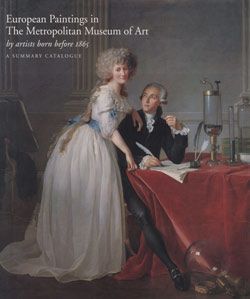

Katharine Baetjer.

European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art by Artists Born in or before 1865: A Summary Catalogue. New York, 1980, p. 118, ill. p. 340.

Guy Bauman in

The Jack and Belle Linksy Collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1984, p. 68.

Stephen H. Goddard.

The Master of Frankfurt and His Shop. Verhandelingen van de Koninklijke Academie voor Wetenschappen, Letteren en Schone Kunsten van België. Klasse der Schone Kunsten 46, no. 38. Brussels. Originally the author’s Ph.D. dissertation, University of Iowa, Iowa City, 1983. 1984, pp. 90-91, 93-94, 111, 113, 116, 134-35, no. 17.

Stephen H. Goddard. "Brocade Patterns in the Shop of the Master of Frankfurt: An Accessory to Stylistic Analysis."

Art Bulletin 67 (1985), pp. 409, 416, fig. 12.

Peter C. Sutton.

Northern European Paintings in the Philadelphia Museum of Art from the Sixteenth through the Nineteenth Century. Philadelphia, 1990, p. 297.

Katharine Baetjer.

European Paintings in The Metropolitan Museum of Art by Artists Born before 1865: A Summary Catalogue. New York, 1995, p. 263, ill.

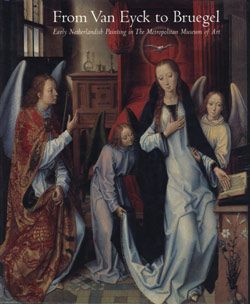

From Van Eyck to Bruegel: Early Netherlandish Painting in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Ed. Maryan W. Ainsworth and Keith Christiansen. Exh. cat., The Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York, 1998, p. 246, ill. p. 247.

Ulrike Wolff-Thomsen.

Jan Joes von Kalkar. Ein niederländischer Maler um 1500. Bielefeld, 1997, pp. 359, ill. p. 357.

Jacqueline Folie. Review of Ulrike Wolff-Thomsen:

Jan Joest von Kalkar: ein niederländischer Maler um 1500. Revue belge d’archéologie et d’histoire de l’art, publ. par l’Académie Royale d’Archéologie de Belgique Bruxelles 66 (1997), pp. 230-233.

Susan Urbach.

Early Netherlandish Paintings. Vol. 2. Szépmüvészeti Múzeum, Budapest, Harvey Miller Publishers, 2015. p. 122-124.

Heck, Christian, Herveì Boëdec, Delphine Adams, and Astrid Bollut.

Collections Du Nord-Pas-De-Calais: La Peinture De Flandre Et De France Du Nord Au Xve Et Au Deìbut Du Xvie SieÌcle. Bruxelles, 2005, pp. 347-54, cat. 48.