Emperor Antoninus Pius

Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi was principal court sculptor to the Gonzaga family, princely rulers of the northern Italian marquisate of Mantua. When collecting Greek and Roman statuary, coins, and precious gems was an essential part of the Renaissance revival of antiquity, Pier Jacopo earned the name l’Antico (“one of the ancients”) for his profound knowledge of classical sculpture.[1] His opulent bronzes, such as this stunning lifesized portrait of the Roman emperor Antoninus Pius, were so convincingly classical in style that the Gonzaga displayed them as “surrogate antiques” among their magnificent collections of ancient art.[2] Antico’s works also gave expressive form to the writings of classical authors esteemed by the Gonzaga. Antoninus Pius, for example, evocatively manifests Pliny the Elder’s description of portraits of exemplary men “of gold or silver [or] at least of bronze” as “immortal spirits who speak to us.”[3] Perhaps most of all, within the politically charged antiquarian culture at the Mantuan court, Antoninus Pius celebrated the Gonzaga’s identification with Imperial Rome and its ruling traditions of virtue, splendor, and power.

Antico’s immaculately executed classicizing bronzes have long excited the imagination of scholars. Today it is generally agreed that the master developed his groundbreaking art by harnessing an unusually diverse combination of technical and formal expertise. Through training as a goldsmith, he acquired the abilities to become the first sculptor since antiquity to employ the indirect method of bronze casting.[4] His bronzes’ colorful surface embellishments of burnished gold, brilliant silver, and velvet black reveal a goldsmith’s wide-ranging technical inventiveness.[5] By studying ancient statuary and restoring fragmentary marble figures in Rome, Antico developed the formal foundation for his revival of classical genres such as the bronze statuette and portrait bust.[6] The Met’s superb collection represents these types with three statuettes—the Spinario, Paris, and Satyr (cats. C9–C11)—and the bust of Antoninus Pius. Although these works have played a key role in advancing our knowledge regarding the master’s artistic development under the aegis of his Gonzaga patrons, fundamental questions about them remain. For example, we are still uncertain why, when, or for whom Antico made the bust.

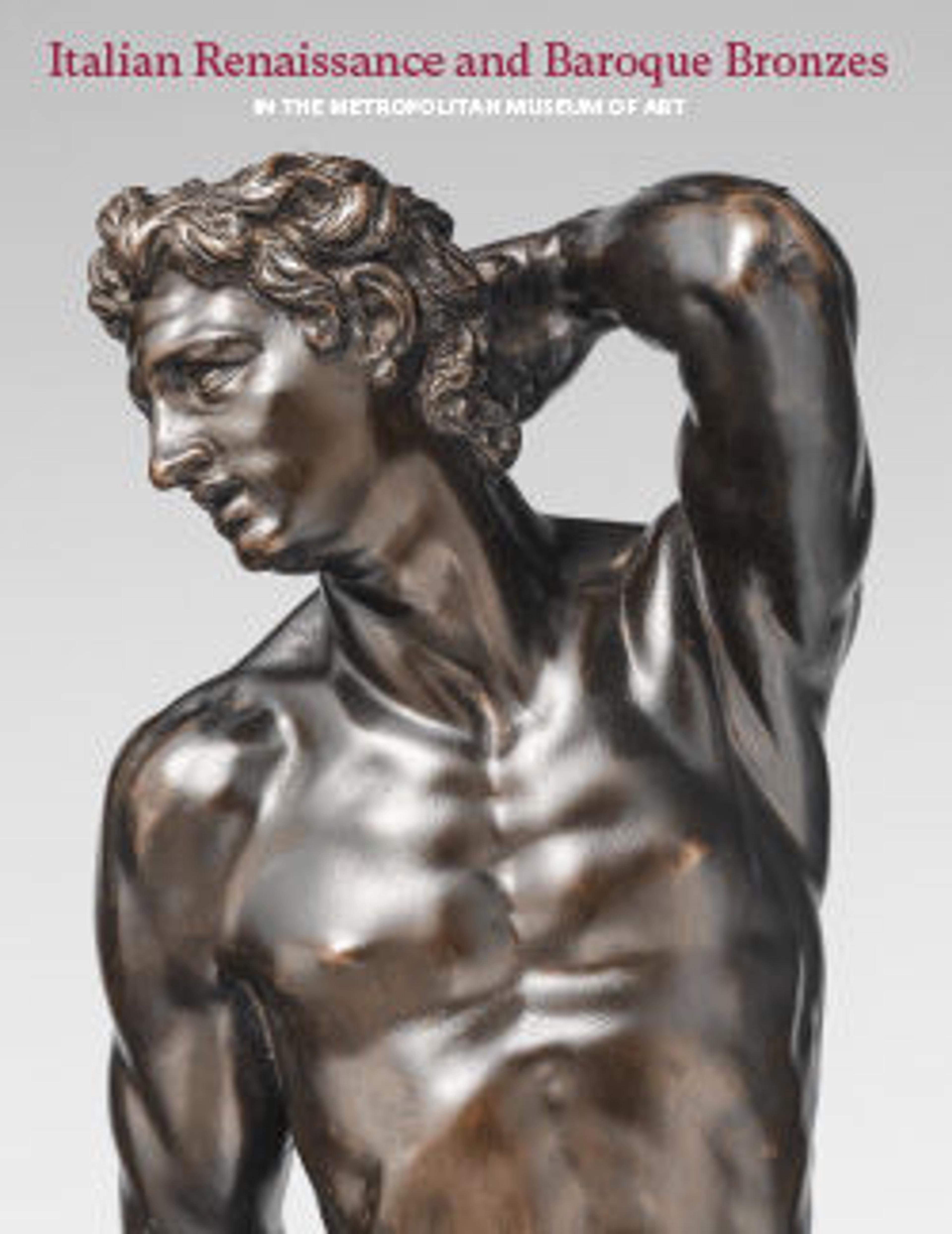

Antico depicts the emperor (r. 138–161 C.E.) in Roman costume wearing a crown of gilded laurel leaves and a draped mantle clasped at the right shoulder. The refined features, framed by abundant curls and a full beard, reflect those found in the emperor’s marble bust-length state portraits, such as the superlative example in Munich (fig. 12a). Antico unusually portrayed the emperor twice, and his interpretations of Antoninus’s official marble bust reveal a change in his development as a portraitist. His earliest bronze head of Antoninus (fig. 12b), completed by 1511 for Bishop-Elect Ludovico Gonzaga, is a straightforward record of the emperor’s physiognomy.[7] By contrast, in our bust Antico focused on the emperor’s psychological state. Through the coloristic syncopation of bronze, silver, and gold, the sculptor heightened the portrait’s expressive power. The emperor’s searing gaze is amplified by shockingly large, light brown eyes that are set off with whites of inlaid silver. The emperor’s concern is registered in the nuanced rendering of the raised brows and furrowed forehead that, combined with the slight turn of the head and shoulders, promise incipient action. In this remarkable work, Antico captured the physical likeness of Antoninus while at the same time projecting the alert intelligence of a man who was revered as one of Rome’s “Good Emperors.”

Antico’s emphasis on Antoninus’s transitory expression was an artistic choice that departs from the constant equanimity for which the emperor was praised. According to his sole surviving classical biography, in the Historia Augusta, Antoninus ruled serenely and was granted the exceptional title “Pius” for the filial devotion he showed to his predecessor.[8] The discrepancy between Antoninus’s sovereign composure described in the classical text and Antico’s compelling bronze is notable because the Gonzaga owned a copy of the Historia Augusta.[9] Moreover, Antico’s other portrait busts of historical and mythological figures are generally self-contained and calm in mood.[10] Among them, Antoninus Pius is a dramatic outlier. Although such unusually vivid animation could have sprung from the sculptor’s close study of an exceptionally fine marble prototype, it also could suggest something more. Of the Gonzaga rulers whom Antico served, only the last, Federico II, demanded that the portrait busts of famous military leaders—which he sought to commission in 1526—be as “true to life as possible.”[11]

In 1524, Antico received steel files and chisels from Federico’s munitions in order to finish or chase (netar) “the head of Antoninus Pius.”[12] But simply identifying The Met portrait as Federico’s commission is complicated by the existence of another cast now in the Louvre.[13] Arguments regarding when and for whom each bust was made roughly divide into two camps. The extreme artistic refinement of our portrait has led some scholars to group it with similarly exquisite busts associated with the taste of Federico’s mother, Isabella d’Este, who was Antico’s principal patron during the late 1510s. They accordingly date it to around these years and connect the less refined Louvre version to the document of 1524 or place it after Antico’s death.[14] Other scholars date The Met Antoninus Pius to 1524 because of its superlative display of techniques. Cast in one piece in a single bravura pour and exhibiting sublime tooling and finishing, it manifests the full range of the master’s virtuosic skills.[15] By contrast, the head and chest of the Louvre Antoninus Pius were cast separately. This cautious casting technique suggests a transitional work created sometime between Antico’s earliest portrait heads, completed by 1511, and our bust, finished in 1524. On the other hand, based on facture, the Louvre version could be a posthumous variant.[16] At present, documentary research, formal analysis, and the evidence presented in recent technical studies have not provided a definitive answer to the patronage/dating conundrum. Offered below are some further observations that might strengthen the case for Federico as the patron of The Met Antoninus Pius.

The initial phase of Federico’s reign (1519–24) challenged established artists at the Mantuan court to develop a new antiquarian style tailored to fit the sophisticated demands of an ambitious young ruler who had been schooled since childhood in the Gonzaga practice of targeting artistic commissions to advance political agendas.[17] Seeking to commission lifelike portraits of exemplary military men in 1526, for example, probably was a means by which Federico conveyed his reinvigoration of Gonzaga rule. Antico’s last documented work, the Antoninus Pius of 1524, could have been the first historical portrait made for Federico that communicated this animated message of renewal. Choosing Antoninus Pius as the portrait’s subject also celebrates the revitalization of Gonzaga tradition. The bust simultaneously embodies the family’s deep-rooted association with the heritage of Imperial Rome and identifies the young marquis with a newcomer to Mantua’s traditional pantheon of emperors.[18] One has to wait until 1511 for a portrait of Antoninus to appear among the eclectic selection of bronze and marble busts of famous men that Antico designed for display in the forecourt of Ludovico’s palace.19 Moreover, unlike the portrait of 1511 or any of the Roman marble prototypes, The Met Antoninus Pius is crowned with laurel leaves. Probably added to signal the bust’s association with Mantua’s new princely ruler, the laurel crown also provides a clue to a significant, unnoticed ancient source for the portrait.

When viewed in profile, Antoninus’s sharp features, elongated neck, and laurel-leaf crown unmistakably mirror the emperor’s official numismatic portraits (fig. 12c).[20] The depiction would have been well known to the Gonzaga, who amassed huge collections of ancient coins.[21] It was especially familiar to Antico, who had based the compositions of his four roundels depicting the Labors of Hercules on the reverses of a rare Alexandrian series of sestertii bearing the portrait of Antoninus.[22] In no other bust does Antico cleave so closely to a numismatic prototype. His faithful quotations add to the portrait another crucial dimension of classical authenticity, for Renaissance audiences believed that the images and inscriptions on ancient coins most accurately preserved the ancient historical record.[23] His extraordinary translation of a small-scale profile in relief into a lifesized bronze bust would have appeared to bring Antoninus powerfully and truthfully to life. The bust’s martial accoutrements—laurel victory crown, clasped military cloak—balance the Historia Augusta’s record of the emperor’s remarkably peaceful reign. The portrait bust thus brilliantly evokes the full scope of imperial history as handed down in Antoninus’s classical biography, numismatic imagery, and marble victory column in Rome.[24] By portraying an emperor who preserves peace through martial readiness, Antico created an ideal portrait of an exemplary ruler with whom Federico, a soldier-prince, could identify.

Federico probably exploited his physical similarity to Antoninus: both were famously vigorous, handsome, bearded men.[25] Federico’s resemblance to Antoninus on the obverse of the first gold coin minted during his reign, the two-ducat doppio d’oro, is notable.[26] By choosing Antoninus as his imperial avatar in portrait busts and on Mantuan coinage, the young marquis associated the character and conduct of his rule with that of the emperor’s. On the doppio d’oro, the intimate linkage between the two rulers’ principles of governance is conveyed in numismatic language. On the coin’s reverse, above an image of Mount Olympus symbolizing the highest aspirations, is inscribed FIDES. This ancient Roman pledge of mutual devotion between a ruler and his people resonates with the filial devotion celebrated by the honorific title “Pius” awarded to one of Rome’s greatest emperors.

Completed in 1524, The Met Antoninus Pius marks the watershed year that Federico turned away from the generation of court artists, Antico among them, who had served his parents and engaged Raphael’s foremost pupil, Giulio Romano, to become Mantua’s new artistic impresario. Against the grand backdrop of ancient Rome re-created through Giulio’s hyperbolic artistic lens at Federico’s new villa, the Palazzo Te, Antico’s philologically accurate, antiquarian sculptures took on the aura of historical artifacts. Outdated in style, they gained validity as “antiquities” to become symbolic foundation stones of Gonzaga rule. The possible display of the Louvre version of Antico’s Antoninus Pius and its companion portrait of the emperor’s wife Faustina above the main entrances to Giulio’s frescoed Sala di Troia (completed in the 1530s) testifies to the imperial couple’s importance to the Gonzaga’s self-fashioned role within a majestic historical narrative.[27] Antico’s Louvre portraits presided over a room decorated with grandiloquent frescoes commemorating the Trojan War, the transformational conflict that led to the foundation of Imperial Rome and ultimately to the establishment of the Gonzaga dynasty and its triumph under Federico II.[28]

-DA

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. For Antico’s biography, see Luciano 2011, pp. 1–14. The documents related to Antico are published in full in Ferrari 2008, pp. 300–328.

2. V. Avery 2007b.

3. Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 25.2.9–10, as cited in Cohen 2002, p. 268.

4. For Antico’s bronze-casting technique, see Stone 1981; D. Smith and Sturman 2011.

5. For a technical study of Antico’s distinctive black patination, see Stone 2011.

6. See Kryza-Gersch 2011; Gasparotto 2011b.

7. Ancient Roman portrait busts most often survived as fragmentary heads; for example, see MMA, 33.11.3.

8. Historia Augusta, trans. David Magie (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1921), vol. 1, pp. 74.

9. Wardropper 2011, p. 56.

10. All of the portrait busts currently attributed to Antico are illustrated in color in Luciano 2011. 11. As cited in and translated by V. Avery 2007b, pp. 90, 106–7, doc. 2.

12. As cited and translated by Luciano 2011, p. 194. The document of July 19, 1524, is published in full in Ferrari 2008, p. 320, doc. 99.

13. Louvre, CAT 1922.849. The Louvre bust was cleaned before its presentation in the Mantua 2008 exhibition, leading to a reassessment of its quality, which previously had been considered mediocre at best. Marc Bormand provides an excellent summary of the complicated issues of dating presented by The Met and Louvre busts in Trevisani and Gasparotto 2008, pp. 266–69, cat. VII.5.

14. For this dating, see Wardropper 2011, pp. 56, 59.

15. For a casting diagram, see Luciano 2011, p. 183.

16. For the discussion outlined here of how the facture and finish of the Louvre and Met busts could suggest their dating, see D. Smith and Sturman 2011, pp. 158–63.

17. The importance of Federico’s innovative artistic agenda during the early or so-called transitional phase of his rule is treated in Mattei 2016.

18. Antoninus Pius, for example, is conspicuously absent from the eight fictive marble busts of the Caesars, derived from Suetonius’s Lives, that decorate the ceiling of the famous audience chamber (camera picta) in the Castello di San Giorgio, Mantua, that Andrea Mantegna frescoed between 1465 and 1474.

19. For this series, see Trevisani 2008.

20. Significantly, the emperor’s iconic numismatic profile portrait was illustrated in Andrea Fulvio’s Illustrium imagines (Rome, ca. 1517), pl. LXXI, shortly before Antico designed the bust of Antoninus Pius. For the relationship between ancient numismatic portraits and Renaissance busts, see Marcello Calogero’s forthcoming doctoral thesis, Scuola Normale di Pisa.

21. See Luciano 2011, p. 2.

22. Antico’s reliance on the reverses of ancient coins to design two of the four Labors of Hercules roundels was first noted in Luciano 2011, pp. 4–6. However, all four roundels derive from the rare Labors of Hercules series bearing the emperor’s portrait. For the series, see Toynbee 1925; Milne 1950.

23. See Scher 2019, pp. 15–17.

24. Until 1703, one of the most important surviving Imperial monuments in Rome, the marble victory column of Marcus Aurelius, was misidentified as the column of Antoninus Pius; see Ridley 2018, p. 240.

25. First noted by Allison 1993–94. See Wardropper 2011, pp. 56–59.

26. See Balbi de Caro 1995, p. 239, R20 and 21, p. 256, pl. 47.

27. Allison 1993–94 first suggested that the Louvre portraits were displayed in the Sala di Troia; see Bormand in Trevisani and Gasparotto 2008, pp. 266–69.

28. For an iconographic interpretation, see Talvacchia 1986.

Antico’s immaculately executed classicizing bronzes have long excited the imagination of scholars. Today it is generally agreed that the master developed his groundbreaking art by harnessing an unusually diverse combination of technical and formal expertise. Through training as a goldsmith, he acquired the abilities to become the first sculptor since antiquity to employ the indirect method of bronze casting.[4] His bronzes’ colorful surface embellishments of burnished gold, brilliant silver, and velvet black reveal a goldsmith’s wide-ranging technical inventiveness.[5] By studying ancient statuary and restoring fragmentary marble figures in Rome, Antico developed the formal foundation for his revival of classical genres such as the bronze statuette and portrait bust.[6] The Met’s superb collection represents these types with three statuettes—the Spinario, Paris, and Satyr (cats. C9–C11)—and the bust of Antoninus Pius. Although these works have played a key role in advancing our knowledge regarding the master’s artistic development under the aegis of his Gonzaga patrons, fundamental questions about them remain. For example, we are still uncertain why, when, or for whom Antico made the bust.

Antico depicts the emperor (r. 138–161 C.E.) in Roman costume wearing a crown of gilded laurel leaves and a draped mantle clasped at the right shoulder. The refined features, framed by abundant curls and a full beard, reflect those found in the emperor’s marble bust-length state portraits, such as the superlative example in Munich (fig. 12a). Antico unusually portrayed the emperor twice, and his interpretations of Antoninus’s official marble bust reveal a change in his development as a portraitist. His earliest bronze head of Antoninus (fig. 12b), completed by 1511 for Bishop-Elect Ludovico Gonzaga, is a straightforward record of the emperor’s physiognomy.[7] By contrast, in our bust Antico focused on the emperor’s psychological state. Through the coloristic syncopation of bronze, silver, and gold, the sculptor heightened the portrait’s expressive power. The emperor’s searing gaze is amplified by shockingly large, light brown eyes that are set off with whites of inlaid silver. The emperor’s concern is registered in the nuanced rendering of the raised brows and furrowed forehead that, combined with the slight turn of the head and shoulders, promise incipient action. In this remarkable work, Antico captured the physical likeness of Antoninus while at the same time projecting the alert intelligence of a man who was revered as one of Rome’s “Good Emperors.”

Antico’s emphasis on Antoninus’s transitory expression was an artistic choice that departs from the constant equanimity for which the emperor was praised. According to his sole surviving classical biography, in the Historia Augusta, Antoninus ruled serenely and was granted the exceptional title “Pius” for the filial devotion he showed to his predecessor.[8] The discrepancy between Antoninus’s sovereign composure described in the classical text and Antico’s compelling bronze is notable because the Gonzaga owned a copy of the Historia Augusta.[9] Moreover, Antico’s other portrait busts of historical and mythological figures are generally self-contained and calm in mood.[10] Among them, Antoninus Pius is a dramatic outlier. Although such unusually vivid animation could have sprung from the sculptor’s close study of an exceptionally fine marble prototype, it also could suggest something more. Of the Gonzaga rulers whom Antico served, only the last, Federico II, demanded that the portrait busts of famous military leaders—which he sought to commission in 1526—be as “true to life as possible.”[11]

In 1524, Antico received steel files and chisels from Federico’s munitions in order to finish or chase (netar) “the head of Antoninus Pius.”[12] But simply identifying The Met portrait as Federico’s commission is complicated by the existence of another cast now in the Louvre.[13] Arguments regarding when and for whom each bust was made roughly divide into two camps. The extreme artistic refinement of our portrait has led some scholars to group it with similarly exquisite busts associated with the taste of Federico’s mother, Isabella d’Este, who was Antico’s principal patron during the late 1510s. They accordingly date it to around these years and connect the less refined Louvre version to the document of 1524 or place it after Antico’s death.[14] Other scholars date The Met Antoninus Pius to 1524 because of its superlative display of techniques. Cast in one piece in a single bravura pour and exhibiting sublime tooling and finishing, it manifests the full range of the master’s virtuosic skills.[15] By contrast, the head and chest of the Louvre Antoninus Pius were cast separately. This cautious casting technique suggests a transitional work created sometime between Antico’s earliest portrait heads, completed by 1511, and our bust, finished in 1524. On the other hand, based on facture, the Louvre version could be a posthumous variant.[16] At present, documentary research, formal analysis, and the evidence presented in recent technical studies have not provided a definitive answer to the patronage/dating conundrum. Offered below are some further observations that might strengthen the case for Federico as the patron of The Met Antoninus Pius.

The initial phase of Federico’s reign (1519–24) challenged established artists at the Mantuan court to develop a new antiquarian style tailored to fit the sophisticated demands of an ambitious young ruler who had been schooled since childhood in the Gonzaga practice of targeting artistic commissions to advance political agendas.[17] Seeking to commission lifelike portraits of exemplary military men in 1526, for example, probably was a means by which Federico conveyed his reinvigoration of Gonzaga rule. Antico’s last documented work, the Antoninus Pius of 1524, could have been the first historical portrait made for Federico that communicated this animated message of renewal. Choosing Antoninus Pius as the portrait’s subject also celebrates the revitalization of Gonzaga tradition. The bust simultaneously embodies the family’s deep-rooted association with the heritage of Imperial Rome and identifies the young marquis with a newcomer to Mantua’s traditional pantheon of emperors.[18] One has to wait until 1511 for a portrait of Antoninus to appear among the eclectic selection of bronze and marble busts of famous men that Antico designed for display in the forecourt of Ludovico’s palace.19 Moreover, unlike the portrait of 1511 or any of the Roman marble prototypes, The Met Antoninus Pius is crowned with laurel leaves. Probably added to signal the bust’s association with Mantua’s new princely ruler, the laurel crown also provides a clue to a significant, unnoticed ancient source for the portrait.

When viewed in profile, Antoninus’s sharp features, elongated neck, and laurel-leaf crown unmistakably mirror the emperor’s official numismatic portraits (fig. 12c).[20] The depiction would have been well known to the Gonzaga, who amassed huge collections of ancient coins.[21] It was especially familiar to Antico, who had based the compositions of his four roundels depicting the Labors of Hercules on the reverses of a rare Alexandrian series of sestertii bearing the portrait of Antoninus.[22] In no other bust does Antico cleave so closely to a numismatic prototype. His faithful quotations add to the portrait another crucial dimension of classical authenticity, for Renaissance audiences believed that the images and inscriptions on ancient coins most accurately preserved the ancient historical record.[23] His extraordinary translation of a small-scale profile in relief into a lifesized bronze bust would have appeared to bring Antoninus powerfully and truthfully to life. The bust’s martial accoutrements—laurel victory crown, clasped military cloak—balance the Historia Augusta’s record of the emperor’s remarkably peaceful reign. The portrait bust thus brilliantly evokes the full scope of imperial history as handed down in Antoninus’s classical biography, numismatic imagery, and marble victory column in Rome.[24] By portraying an emperor who preserves peace through martial readiness, Antico created an ideal portrait of an exemplary ruler with whom Federico, a soldier-prince, could identify.

Federico probably exploited his physical similarity to Antoninus: both were famously vigorous, handsome, bearded men.[25] Federico’s resemblance to Antoninus on the obverse of the first gold coin minted during his reign, the two-ducat doppio d’oro, is notable.[26] By choosing Antoninus as his imperial avatar in portrait busts and on Mantuan coinage, the young marquis associated the character and conduct of his rule with that of the emperor’s. On the doppio d’oro, the intimate linkage between the two rulers’ principles of governance is conveyed in numismatic language. On the coin’s reverse, above an image of Mount Olympus symbolizing the highest aspirations, is inscribed FIDES. This ancient Roman pledge of mutual devotion between a ruler and his people resonates with the filial devotion celebrated by the honorific title “Pius” awarded to one of Rome’s greatest emperors.

Completed in 1524, The Met Antoninus Pius marks the watershed year that Federico turned away from the generation of court artists, Antico among them, who had served his parents and engaged Raphael’s foremost pupil, Giulio Romano, to become Mantua’s new artistic impresario. Against the grand backdrop of ancient Rome re-created through Giulio’s hyperbolic artistic lens at Federico’s new villa, the Palazzo Te, Antico’s philologically accurate, antiquarian sculptures took on the aura of historical artifacts. Outdated in style, they gained validity as “antiquities” to become symbolic foundation stones of Gonzaga rule. The possible display of the Louvre version of Antico’s Antoninus Pius and its companion portrait of the emperor’s wife Faustina above the main entrances to Giulio’s frescoed Sala di Troia (completed in the 1530s) testifies to the imperial couple’s importance to the Gonzaga’s self-fashioned role within a majestic historical narrative.[27] Antico’s Louvre portraits presided over a room decorated with grandiloquent frescoes commemorating the Trojan War, the transformational conflict that led to the foundation of Imperial Rome and ultimately to the establishment of the Gonzaga dynasty and its triumph under Federico II.[28]

-DA

Footnotes

(For key to shortened references see bibliography in Allen, Italian Renaissance and Baroque Bronzes in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2022.)

1. For Antico’s biography, see Luciano 2011, pp. 1–14. The documents related to Antico are published in full in Ferrari 2008, pp. 300–328.

2. V. Avery 2007b.

3. Pliny the Elder, Natural History, 25.2.9–10, as cited in Cohen 2002, p. 268.

4. For Antico’s bronze-casting technique, see Stone 1981; D. Smith and Sturman 2011.

5. For a technical study of Antico’s distinctive black patination, see Stone 2011.

6. See Kryza-Gersch 2011; Gasparotto 2011b.

7. Ancient Roman portrait busts most often survived as fragmentary heads; for example, see MMA, 33.11.3.

8. Historia Augusta, trans. David Magie (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1921), vol. 1, pp. 74.

9. Wardropper 2011, p. 56.

10. All of the portrait busts currently attributed to Antico are illustrated in color in Luciano 2011. 11. As cited in and translated by V. Avery 2007b, pp. 90, 106–7, doc. 2.

12. As cited and translated by Luciano 2011, p. 194. The document of July 19, 1524, is published in full in Ferrari 2008, p. 320, doc. 99.

13. Louvre, CAT 1922.849. The Louvre bust was cleaned before its presentation in the Mantua 2008 exhibition, leading to a reassessment of its quality, which previously had been considered mediocre at best. Marc Bormand provides an excellent summary of the complicated issues of dating presented by The Met and Louvre busts in Trevisani and Gasparotto 2008, pp. 266–69, cat. VII.5.

14. For this dating, see Wardropper 2011, pp. 56, 59.

15. For a casting diagram, see Luciano 2011, p. 183.

16. For the discussion outlined here of how the facture and finish of the Louvre and Met busts could suggest their dating, see D. Smith and Sturman 2011, pp. 158–63.

17. The importance of Federico’s innovative artistic agenda during the early or so-called transitional phase of his rule is treated in Mattei 2016.

18. Antoninus Pius, for example, is conspicuously absent from the eight fictive marble busts of the Caesars, derived from Suetonius’s Lives, that decorate the ceiling of the famous audience chamber (camera picta) in the Castello di San Giorgio, Mantua, that Andrea Mantegna frescoed between 1465 and 1474.

19. For this series, see Trevisani 2008.

20. Significantly, the emperor’s iconic numismatic profile portrait was illustrated in Andrea Fulvio’s Illustrium imagines (Rome, ca. 1517), pl. LXXI, shortly before Antico designed the bust of Antoninus Pius. For the relationship between ancient numismatic portraits and Renaissance busts, see Marcello Calogero’s forthcoming doctoral thesis, Scuola Normale di Pisa.

21. See Luciano 2011, p. 2.

22. Antico’s reliance on the reverses of ancient coins to design two of the four Labors of Hercules roundels was first noted in Luciano 2011, pp. 4–6. However, all four roundels derive from the rare Labors of Hercules series bearing the emperor’s portrait. For the series, see Toynbee 1925; Milne 1950.

23. See Scher 2019, pp. 15–17.

24. Until 1703, one of the most important surviving Imperial monuments in Rome, the marble victory column of Marcus Aurelius, was misidentified as the column of Antoninus Pius; see Ridley 2018, p. 240.

25. First noted by Allison 1993–94. See Wardropper 2011, pp. 56–59.

26. See Balbi de Caro 1995, p. 239, R20 and 21, p. 256, pl. 47.

27. Allison 1993–94 first suggested that the Louvre portraits were displayed in the Sala di Troia; see Bormand in Trevisani and Gasparotto 2008, pp. 266–69.

28. For an iconographic interpretation, see Talvacchia 1986.

Artwork Details

- Title: Emperor Antoninus Pius

- Artist: Antico (Pier Jacopo Alari Bonacolsi) (Italian, Mantua ca. 1460–1528 Gazzuolo)

- Date: 1519–24

- Culture: Italian, Mantua

- Medium: Bronze, partially oil-gilt, silver inlay, on serpentinite socle

- Dimensions: Overall without base (confirmed): H. 25 1/4 x W. 19 3/4 x D. 14 1/4 in. (64.1 x 50.2 x 36.2 cm); Height with base (confirmed): 29 7/8 in. (75.9 cm)

- Classification: Sculpture-Bronze

- Credit Line: Gift of Edward Fowles, 1965

- Object Number: 65.202

- Curatorial Department: European Sculpture and Decorative Arts

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.