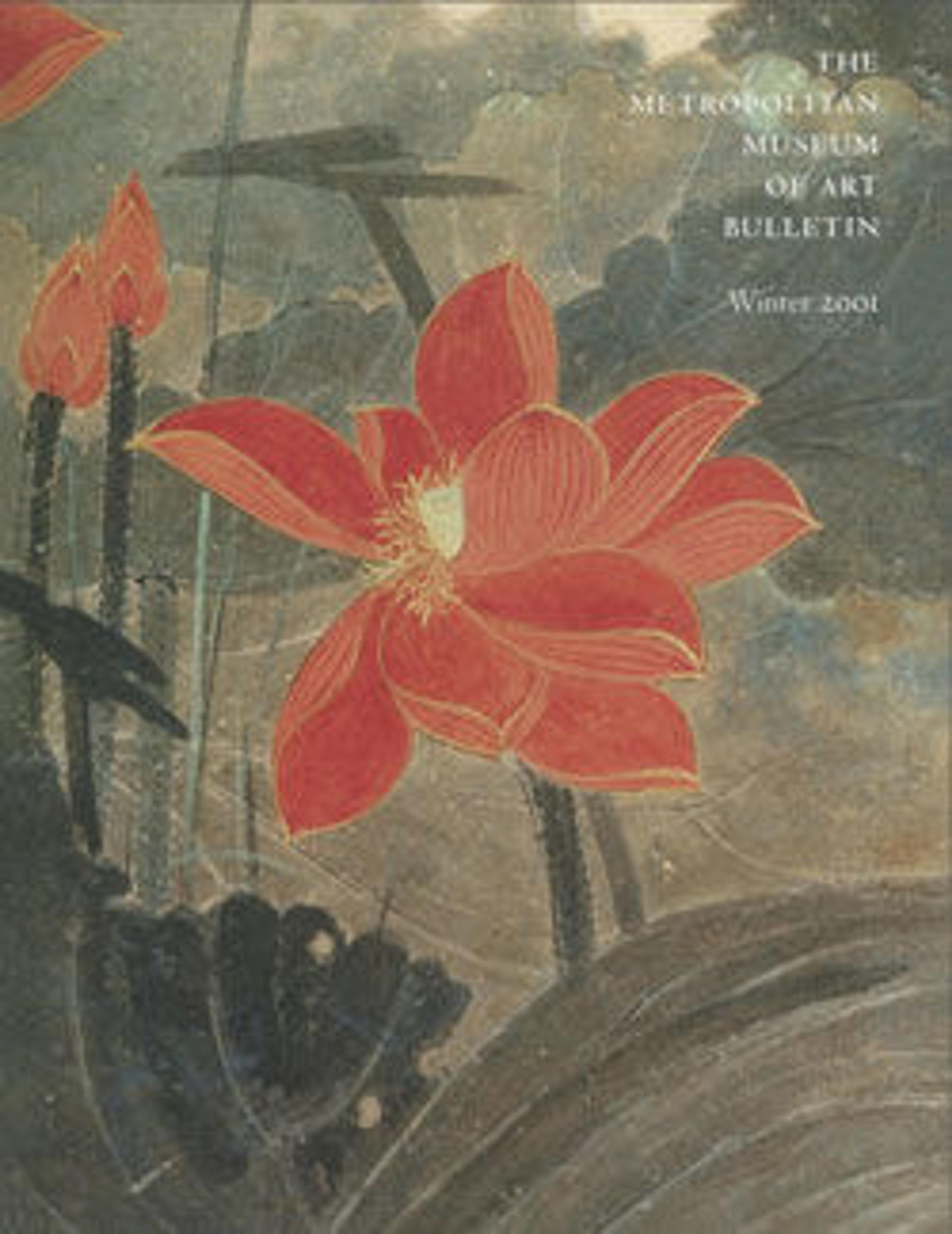

Blossoming plum

A poet, collector, and bibliophile, Jin Nong did not take up painting until the age of fifty. Known as one of the Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou, Jin specialized in painting plum blossoms. He developed a distinctive style of calligraphy through the study of the squat clerical-script form of ancient stele writing.

Blossoming Prunus was painted for a high official only five years before Jin's death at age seventy-two. In his inscription, Jin speaks of the good fortune of the plum painters Yang Buzhi (1097–1169) and Ding Yetang (active mid-13th century), whose works gained imperial recognition. Jin then adds, jestingly:

"Now I, too, have done a likeness of latticed branches and scattered shadows. How might it also enter the Nine Enclosures [of the Forbidden City] and be submitted to imperial view?"

Blossoming Prunus was painted for a high official only five years before Jin's death at age seventy-two. In his inscription, Jin speaks of the good fortune of the plum painters Yang Buzhi (1097–1169) and Ding Yetang (active mid-13th century), whose works gained imperial recognition. Jin then adds, jestingly:

"Now I, too, have done a likeness of latticed branches and scattered shadows. How might it also enter the Nine Enclosures [of the Forbidden City] and be submitted to imperial view?"

Artwork Details

- 清 金農 墨梅圖 軸

- Title: Blossoming plum

- Artist: Jin Nong (Chinese, 1687–1773)

- Period: Qing dynasty (1644–1911)

- Date: dated 1759

- Culture: China

- Medium: Hanging scroll; ink on paper

- Dimensions: Image: 49 3/8 x 17 in. (125.4 x 43.2 cm)

Overall with mounting: 85 1/2 x 21 in. (217.2 x 53.3 cm)

Overall with knobs: 85 1/2 x 23 3/4 in. (217.2 x 60.3 cm) - Classification: Paintings

- Credit Line: Bequest of John M. Crawford Jr., 1988

- Object Number: 1989.363.160

- Curatorial Department: Asian Art

More Artwork

Research Resources

The Met provides unparalleled resources for research and welcomes an international community of students and scholars. The Met's Open Access API is where creators and researchers can connect to the The Met collection. Open Access data and public domain images are available for unrestricted commercial and noncommercial use without permission or fee.

To request images under copyright and other restrictions, please use this Image Request form.

Feedback

We continue to research and examine historical and cultural context for objects in The Met collection. If you have comments or questions about this object record, please contact us using the form below. The Museum looks forward to receiving your comments.