In the academic study of Jewish books and manuscripts, the ketubah כְּתוּבָּה, or Jewish marriage contract, often garners less attention than the more famous manuscript copies of the Tanakh תָּנָ״ךְ, the Megillat Esther, and the Pesach Haggadah. However, these documents occupy a unique place in Jewish cultural arts, functioning simultaneously as religious documents, legal documents, and Jewish folk art. Here at the Thomas J. Watson Library, an array of exhibition catalogs and art history books explore aspects of ketubah art from the history of its development and use to iconography and artistic influences.

Shalom Sabar, Mazal Tov: Illuminated Jewish Marriage Contracts from the Israel Museum Collection (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, [c1993]). Image #39, Page 138

Shalom Sabar, Mazal Tov: Illuminated Jewish Marriage Contracts from the Israel Museum Collection (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, [c1993]). Image #36, Page 132

Professor Shalom Sabar specializes in Jewish art and folklore and is the author or editor of ten books in the Watson Library collection. His book, Mazal Tov: Illuminated Jewish Marriage Contracts from the Israel Museum Collection, stands out among other books on the same subject in deconstructing and centering specific motifs in ketubah art from around the world: the gate motif; depictions of the holy city of Ancient Jerusalem and the temple; the bridal couple; national emblems; and floral and animal motifs. The two pictured above are examples of national emblems from Jewish diasporic communities. The first is a marriage contract from Gibraltar in 1886 depicting a bald eagle, the national bird of the United States, perched on a shield of stars and stripes referring to the U.S. flag. Below is a banner with the U.S. motto, “E Pluribus Unum.” The second is a marriage contract from Isfahan, Iran, in 1898, which features two lions with suns with human faces rising over their backs, the royal emblem of Iranian antiquity. Such visual expressions of loyalty to nations or rulers were perhaps a desire to secure safety and protection for Jewish diasporic communities or a representation of the dual identity of living in the diaspora.

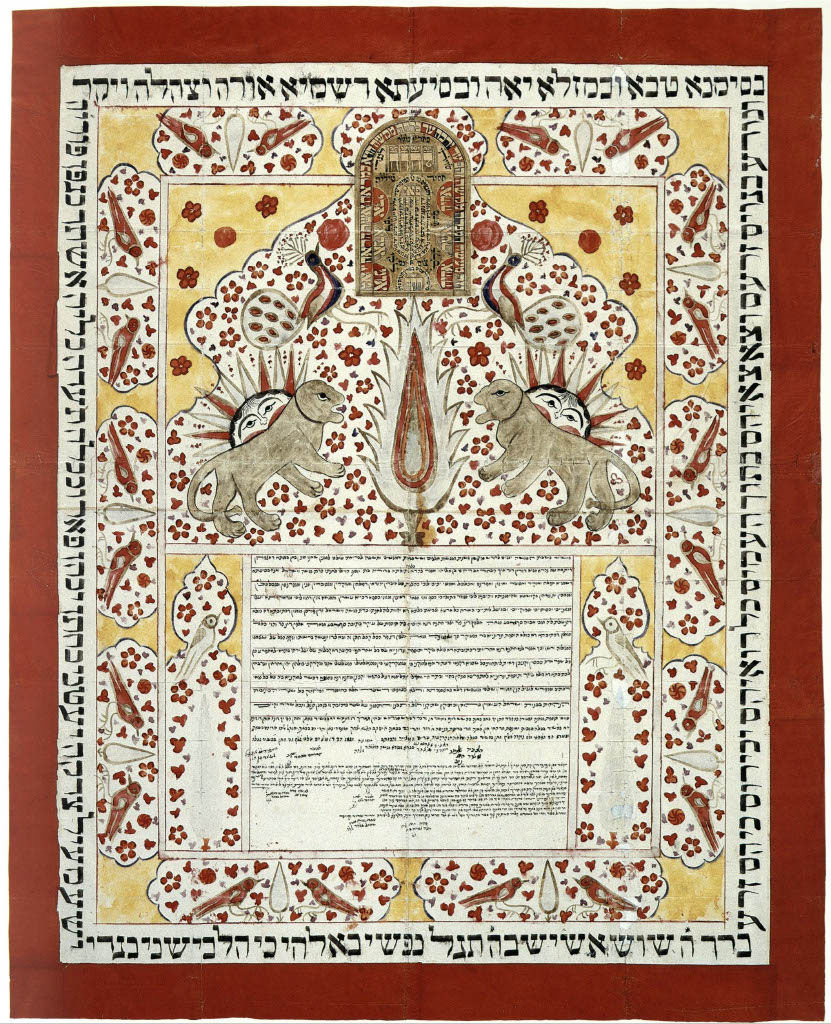

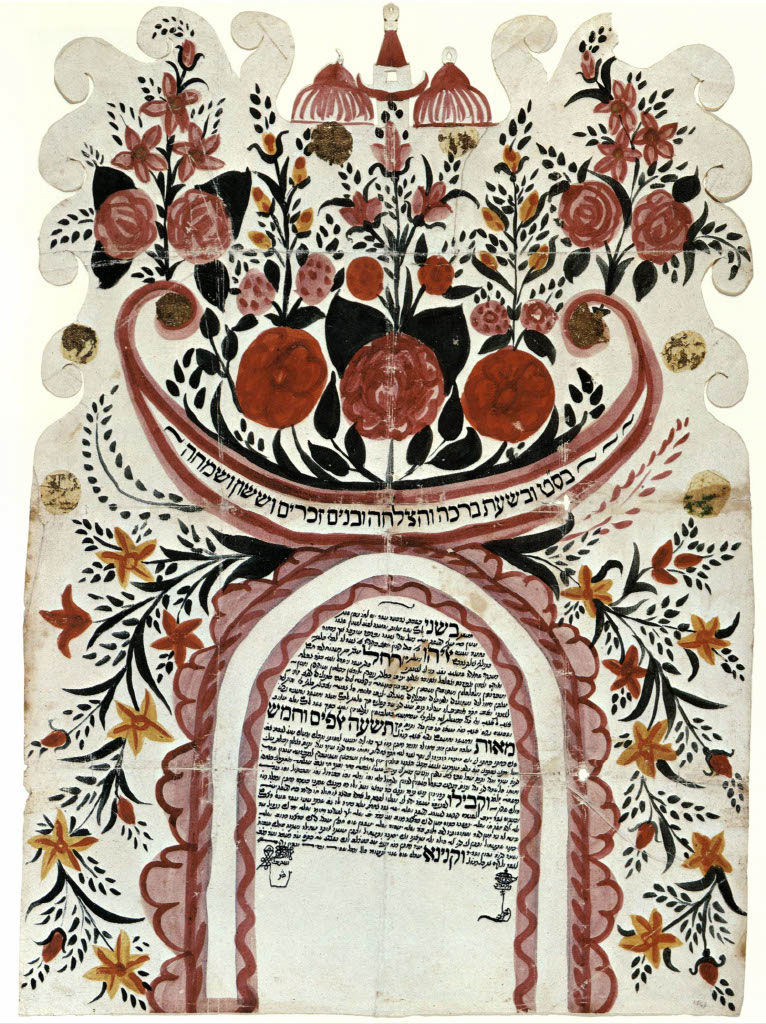

Shalom Sabar, Ketubbah: Jewish Marriage Contracts of the Hebrew Union College Skirball Museum and Klau Library (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, [1990]). Image #246, Page 366

Shalom Sabar, Ketubbah: Jewish Marriage Contracts of the Hebrew Union College Skirball Museum and Klau Library (Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, [1990]). Image #174, Page 273

In another of his books, Ketubbah: Jewish Marriage Contracts of the Hebrew Union College Skirball Museum and Klau Library, Sabar takes an international approach, categorizing ketubot by country of origin and analyzing the styles and techniques unique to each region. The first of the two images above shows a ketubah from a small Moroccan Jewish community in Pará de Brazil in 1911. The colored lithograph printing, as well as the scribal work, are indicative of the Northern African influences on the culture within the community. The second is a ketubah from Bucharest, Romania, under Ottoman rule in 1831. The layout of the ketubah, in two columns of text under arches, draws on European, especially Balkan, influence. However, the floral motifs, imitation of an Ottoman tughra (Turkish seal), and the banner of an imagined script emulating Turkish calligraphy speak to the Ottoman and Turkish cultural presence. In Sabar's text, the ketubot visualize the eternal harmony and balance of dual intercultural inheritance in diasporic communities with Jewish and local styles present yet distinct.

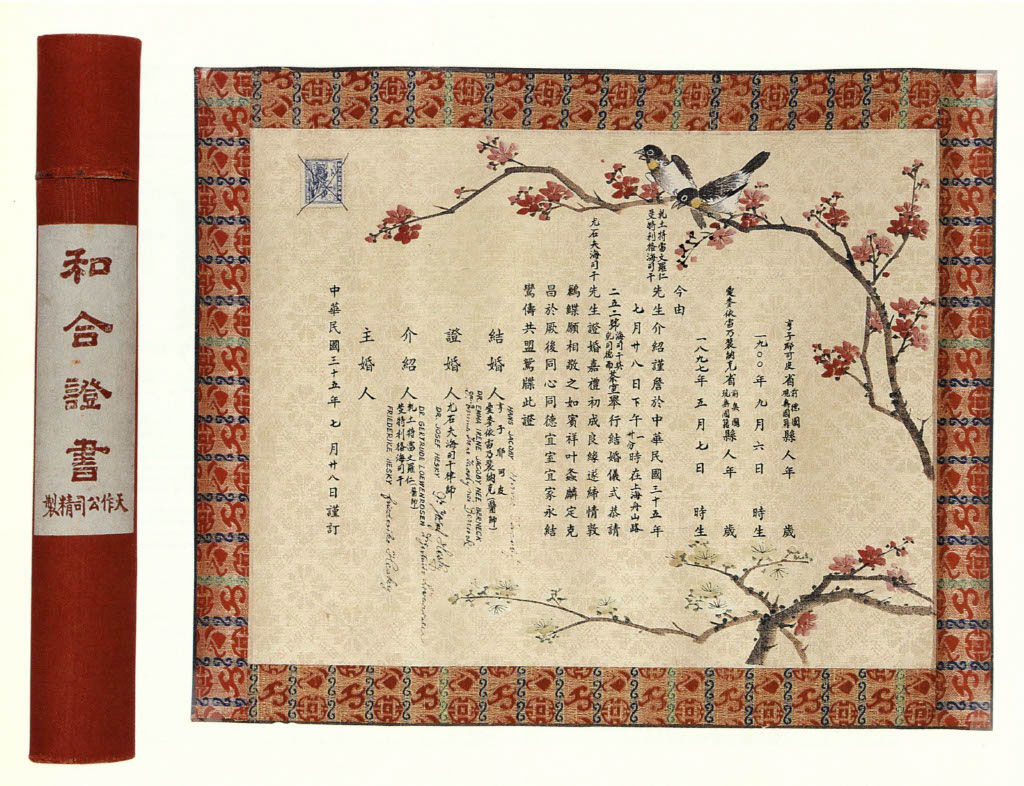

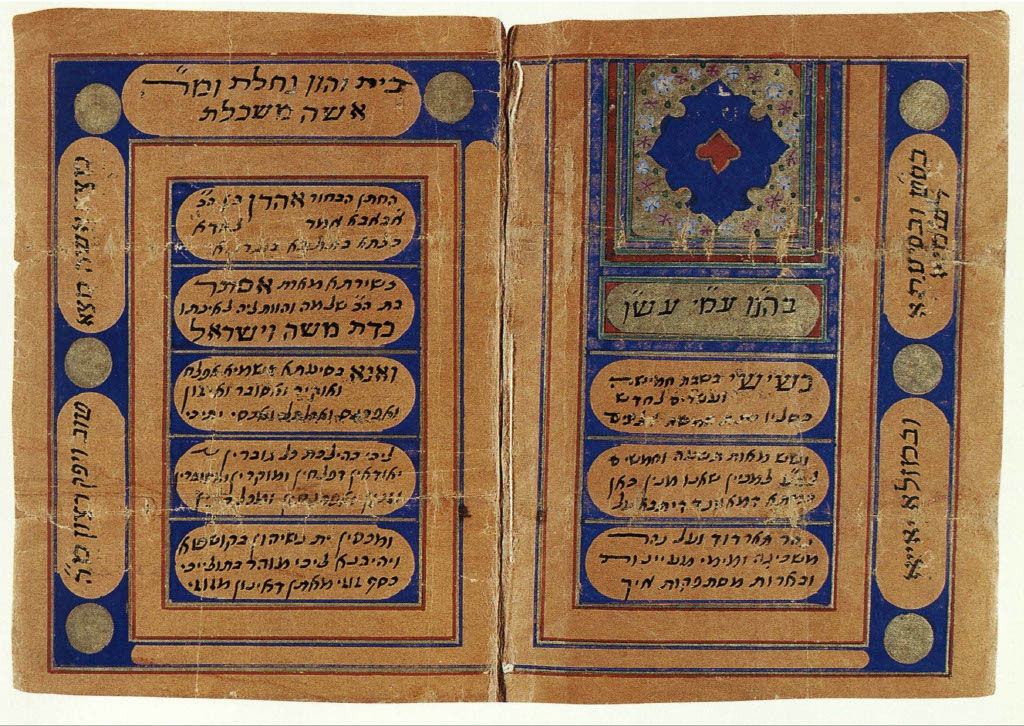

Claudia J. Nahson, Ketubbot: Marriage Contracts from the Jewish Museum (New York: Jewish Museum, under the auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America; San Francisco: Pomegranate, [c1998]). Image #36, Page 58

Claudia J. Nahson, Ketubbot: Marriage Contracts from the Jewish Museum (New York: Jewish Museum, under the auspices of the Jewish Theological Seminary of America; San Francisco: Pomegranate, [c1998]). Image #32, Page 53

The visual motifs are not the only cross-cultural influence in ketubah art. In Ketubbot: Marriage Contracts from the Jewish Museum, another book that takes an international perspective on ketubot, Claudia J. Nahson highlights local influences on the physical structures of ketubot. The first of the two images above is a Shanghainese secular marriage certificate from 1946 in the form of a scroll. Although not a ketubah, the contract demonstrates how historical circumstances, such as fleeing Europe during the Holocaust and local book structures, shaped the forms of Jewish marriage. The second is a ketubah from 1898 in Damavand, Persia, in the form of a booklet, evidenced by the central crease. Such a form was popular in the Jewish community of Tehran and came from the use of booklet marriage contracts among the Muslim community.

Olga Melasecchi and Amedeo Spagnoletto, Antique Roman Ketubot: The Marriage Contracts of the Jewish Community of Rome, translated by Nurit Roded (Roma: Museo Ebraico di Roma: Campisano Editore, [2019]). Image #5, Page 100

Olga Melasecchi and Amedeo Spagnoletto, Antique Roman Ketubot: The Marriage Contracts of the Jewish Community of Rome, translated by Nurit Roded (Roma: Museo Ebraico di Roma: Campisano Editore, [2019]). Image #17, Page 113

There are books on ketubah art in the Watson Library that focus on specific locations rather than taking the international approach of the three previously discussed books. Antique Roman Ketubot: The Marriage Contracts of the Jewish Community of Rome by Olga Melasecchi and Amedeo Spagnoletto focuses on the art styles and techniques of the Jewish scribes and artisans in Rome. Above are two examples from 1737 (top) and 1793 (bottom) of a shape unique to Roman and Italian ketubot, with an elongated and curved bottom edge that once held a ribbon, increasing the ease of rolling and storing the ketubah as a scroll. The curve at the bottom would have been from the skin at the neck of the animal used to make the vellum, and such a shape helped to avoid wasting expensive and valuable vellum, which was labor-intensive to produce.

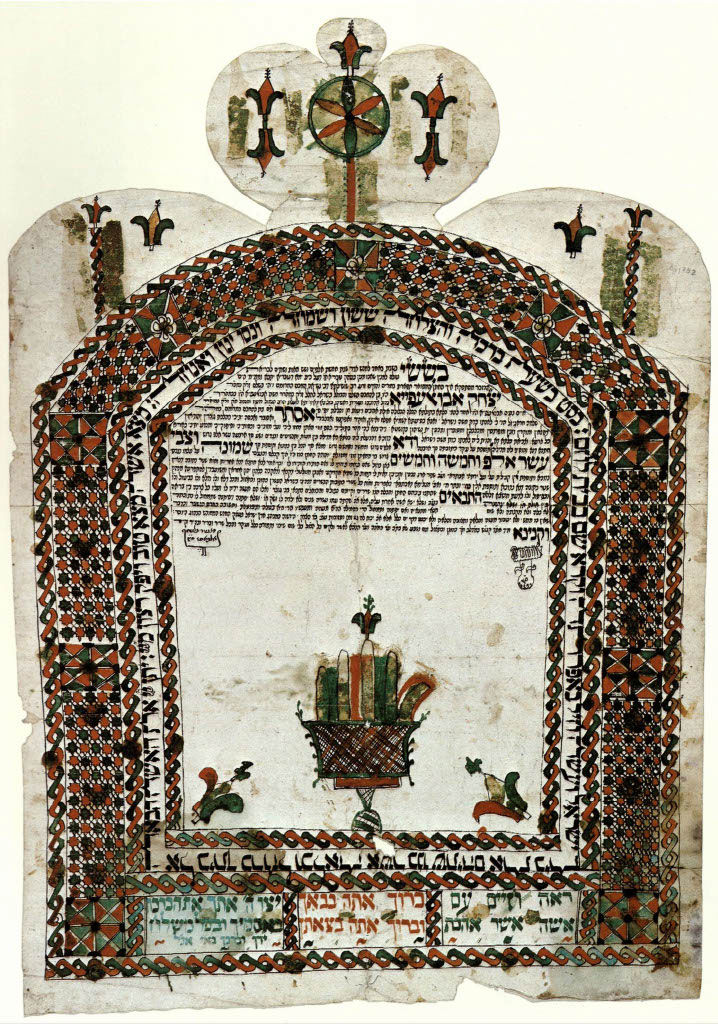

Glenda Milrod, Ketubah, the Jewish Marriage Contract (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, [c1980]). Image #22, Page 31

Glenda Milrod, Ketubah, the Jewish Marriage Contract (Toronto: Art Gallery of Ontario, [c1980]). Image #23, Page 33

However, a unique ketubot shape was not unique to Rome. In Ketubah, the Jewish Marriage Contract, author and curator Glenda Milrod explores ketubot’s history and artistic diversity using examples from her exhibition for the Art Gallery of Ontario in collaboration with the Beth Tzedec Museum. The two pieces pictured above display the unique paper-cut shapes that ketubot could take, adding an extra form of decoration in addition to the calligraphy and painted images. The first is a ketubah from Tiberias in the Galilee region in 1842. The top edge of the paper features cut, round corners and a tri-globed crown in the center—another example of the national emblem motif described by Sabar in Mazal Tov, mentioned above. Milrod also makes note of the hamsa below the text, an ornamented hand of good luck traditionally used in the Ancient Near East. The second image is a ketubah from Damascus, Syria, in 1848. The top and upper sides are cut into elegant spirals, flanking two carved domes and a tower, a representation of ancient Jerusalem in keeping with the Tehillim line, “place Jerusalem at the head of my joy.” Such uniquely shaped ketubot were popular, and the paper carving of these two seem purely decorative, unlike the shaped bottom of the ketubot from Rome mentioned above.

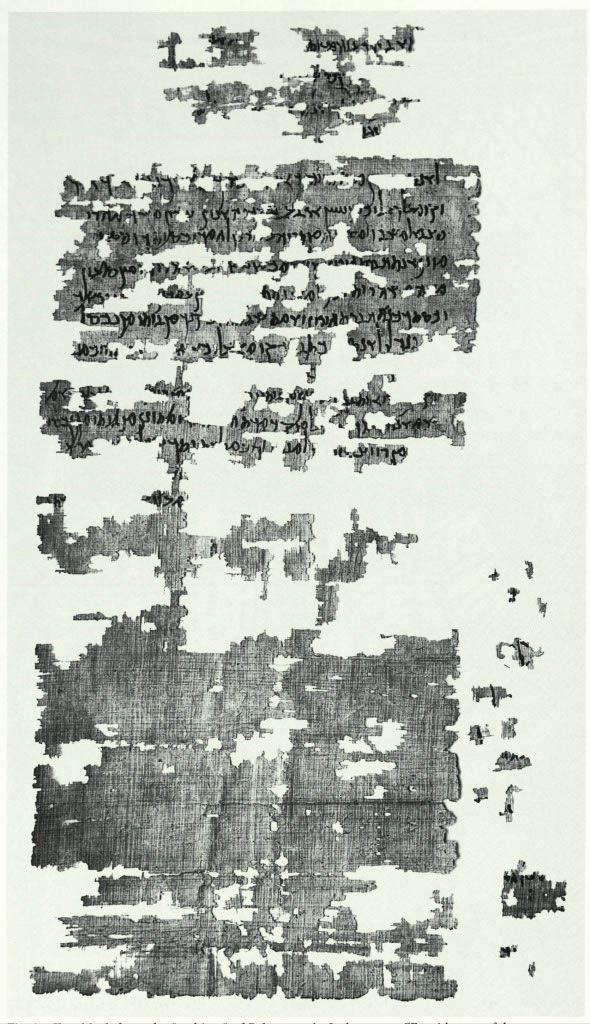

Shalom Sabar, Mazal Tov: Illuminated Jewish Marriage Contracts from the Israel Museum Collection (Jerusalem: Israel Museum, [c1993]). Image #1, Page 10

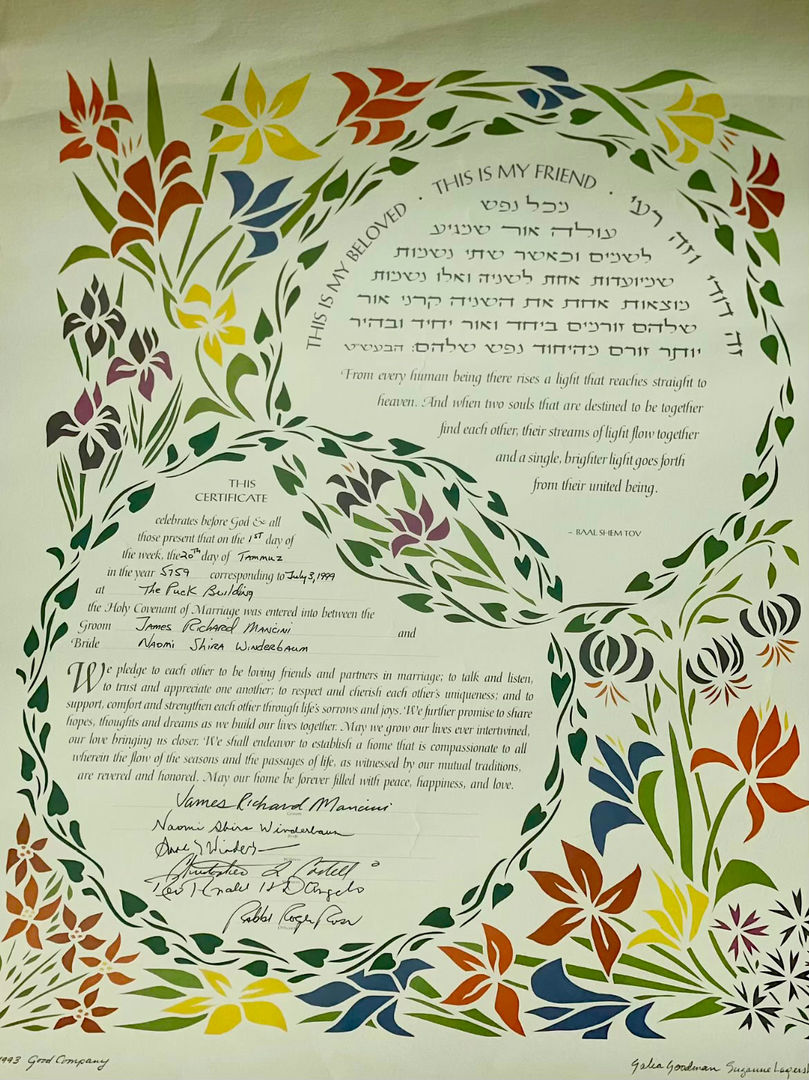

Galia Goodman and Suzanne Lagershausen, Personal Ketubbah of Naomi Winderbaum and James Mancini (New York: Good Company, [1993])

From one of the earliest surviving ketubot, written in ancient Israel in the early second century CE, to the 1999 ketubah hanging in my parents’ own bedroom, Jewish art has decorated and celebrated marriage contracts and Jewish love. The art reflects the people who make and use it, and the culture those people come from. Through these ketubot and the books that study them, we can see Jewish history and traditions across the globe throughout the years, their similarities and differences, and the things they valued and wished to preserve. In researching this project and looking at the ketubot art, I saw reflections of myself and my family—multicultural, with roots across the world, yet still fundamentally Jewish. I saw Jewish art that flourishes and blends with nearby cultures in the diaspora. Jewish art that, like the Jewish people, adapts and thrives, creating beauty in love and peace.