Introduction

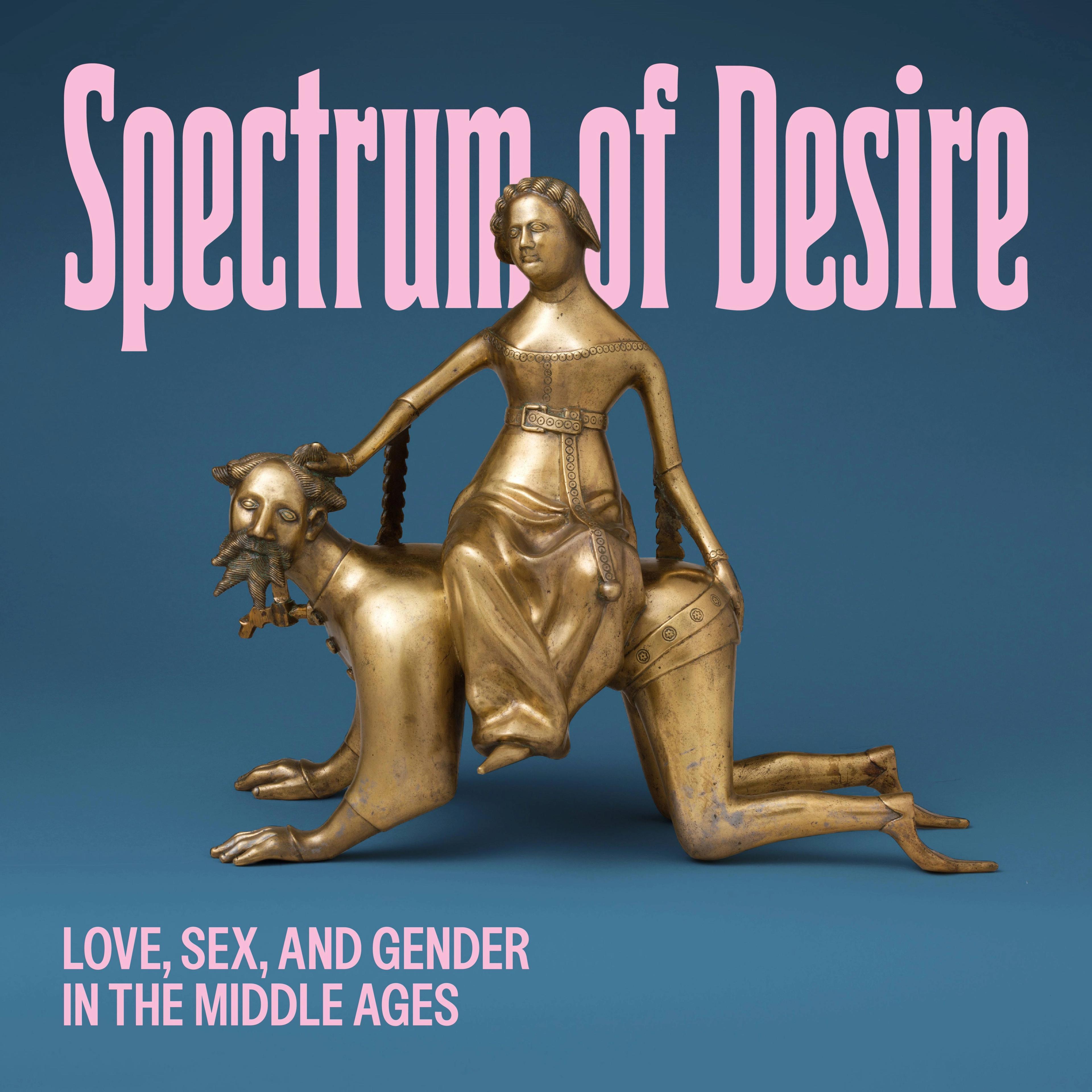

Spectrum of Desire: Love, Sex, and Gender in the Middle Ages

The thirteenth through fifteenth centuries in western Europe saw increasingly restrictive definitions of sex and marriage, particularly under Church law. Art from this period, however, tells a more complex story. Even as some works enforced these tighter regulations, others provided generative settings for exploring and broadening ideas around gender expression, erotic union, and loving kinship.

Often inspired by devotional and literary texts, medieval artists focused on the theme of desire, both physical and spiritual. They recorded a world in which aristocrats modeled the elaborate choreography of courtship, saints declared their wish to be Christ’s bride, and passionate friendships abounded in the homosocial spheres of the court and the monastery.

The feelings expressed in medieval art can be surprising. Its imagery often refuses the rigid distinctions we might make between male and female, friend and lover, profane and sacred. For many today, these refusals will resonate. They encourage the viewer to work against the limits of contemporary categories and presumptions—an approach sometimes described as queering the past. This perspective can uncover new meanings but also make way for moments of ambiguity.

Spectrum of Desire primarily features art from The Met collection, displayed alongside several exceptional loans. Reading beloved masterpieces through the lens of desire can refresh how we think about works that have long been in the public eye and, in turn, invite us to consider our own ideas of love, sex, and gender.

The exhibition is made possible by the Michel David-Weill Fund and Kathryn A. Ploss.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Marriage, Sex, and Chastity

The marital bond between a man and a woman was a consuming medieval ideal, upheld by religious legislation, literature, and art. Gifts were especially integral to wedding rites, their imagery offering expressions of both amorous desire and bleaker visions of domestic life, especially for women. The Church praised procreative sex between a husband and wife but considered any other kind of sex act (no matter the gender of one's partner) sodomia, a vast category of sins that also included religious heresy and subversive gender expression.

For many, not having a partner and not having sex was a deliberate and celebrated choice. Theologians like Saint Augustine deemed abstinence from sexual union more virtuous than sex within marriage. Knights were often exhorted to ignore their sexual impulses. A hierarchy of non-sex emerged, which included virgins and the chaste, those who were celibate, and those who did not experience sexual desire.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Objects of Desire

Medieval people understood objects as potent stimulants of sexual desire. They ignited the imagination and kept the thoughts of a distant lover ever present. One fourteenth-century religious text, for instance, warns of the “carnal lusts” that arise from “comfortable beddings, delicious and soft shirts, and pleasurable robes of scarlet.” Personal goods—such as the belts, combs, writing tablets, jewelry, and small containers on view in this section—were incorporated into the elaborate push-pull of courtship.

Our understanding of medieval love imagery is based on the elaborate fantasies spun by contemporaneous artists, musicians, and storytellers. Through image, song, and verse, they depicted aristocratic young lovers who suffered from obsessive, often adulterous or otherwise impossible, desire. Couples engaged in games that involved the offering and withholding of affection. Here, an electric dynamic of dominance and submission runs through seemingly playful depictions of chin caresses, chess, and hunting.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Beautiful Bodies

Bodies in medieval art are highly expressive. Rather than striving for naturalism, artists aimed to communicate a subject’s identity through specific attributes, including clothing, hair, pose, and skin color. Together, they could evoke multiple aspects of a person’s identity—social class, religion, geographic origin, gender—as well as changes to that identity across time.

In both image and text, bodies were frequently in flux. Bodily change was a central tenet of Christian belief, explored in biblical narratives from the creation of Adam and Eve to the Resurrection of Christ. Medieval theologians and artists understood Christ as having both male and female attributes, for instance, and many saints are said to have changed their gender presentation over the course of their lifetimes. Their images—intended to inspire admiration or, on rare occasions, ridicule—attest to the long history of gender nonconformity.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Mystical Union

Some of the greatest Christian thinkers of the medieval period elaborated in their religious writings on the deep, lingering kisses they sought with the Lord. Today, this pairing of the sacred and the erotic might seem strange, even unsettling. But for those who wanted a spiritual union with God, there was no better language to evoke the rare and intoxicatingly beautiful experience they desired.

Works of art proved especially conducive to expressing and facilitating spiritual ecstasy. Illustrated handbooks offered step-by-step devotional guides, while imposing sculptures could focus one’s concentration or serve as models of ideal unions between the human and divine. Art also promoted an imaginative rethinking of gender identities and forms of kinship that were particularly empowering for nuns and monks. The chosen families created within religious orders could offer deeply satisfying alternatives to the bonds available in the secular world.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.