Divine Egypt

The falcon Horus, lion-headed Sakhmet, shrouded Osiris–the gods of ancient Egypt have captivated the public imagination for centuries. They assume a variety of forms that are sometimes human, sometimes animal, and often both. This is just one aspect of the gods’ iconography, or the visual traits and symbols that identify them. The imagery associated with many deities underwent frequent expansions and adaptations. In a belief system defined by its flexibility, gods could share roles, merge together, and even take on the attributes of other deities.

This exhibition examines ancient Egypt’s principal gods and how worshippers—both royal and not—chose to represent them. In a civilization that lasted some three thousand years and stretched more than eight hundred miles along a river valley, change in religious belief over time and diversity in local traditions were commonplace.

From small amulets to monumental temple sculptures, the works on display here invite us to consider ancient Egypt through the lens of its own religion. The roles and appearances of the gods offer an important window onto how the people who created them attempted to make sense of their complex and ever-changing world.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Expressing the Divine

The deities Hathor and Horus have been chosen to introduce the complexity of the ancient Egyptian divine landscape and demonstrate the types of characteristics and symbols that can identify a divine image. Both gods originated early in Egyptian history, Horus by about 3100 BCE and Hathor by about 2600 BCE, and appeared throughout ancient temples, shrines, and tombs. Hathor has numerous manifestations, while Horus’s imagery is remarkably consistent. Over time, their symbols and traits were given to many other deities.

Hathor, a goddess usually shown with a head ornament composed of cow horns and a sun disk, is among a small group of deities who take distinct forms to serve particular roles. These varying aspects reflect both Hathor’s long-standing importance and her responsibility for multiple aspects of Egyptian life.

Horus defines kingship, and the pharaoh consistently identified with him. Horus’s use of falcon imagery is not unique, however, and other gods—Re-Harakhty, Montu, and Sokar, for example—can also appear as a falcon-headed man.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Ruling the Cosmos

Re, the sun god, brings forth life. He is conceptualized as the supreme god and ruler of all. The recurring cycle of his birth in the morning, journey across the sky during the day, and voyage through the underworld at night preserves the cosmic order and thus keeps the world in maat, a unique Egyptian conception of “what is right.” Through this perpetual process, he brings warmth and light to the world and allows humans to be reborn in the afterlife. His iconography varies to reflect different times of the day.

A number of gods assist Re in carrying out his responsibilities. Maat, the embodiment of “what is right,” wears an ostrich feather against which every soul is weighed. The ibis-headed Thoth is a divine scribe and healer. With the head of a composite animal, multifaceted Seth can be both a protector and a rival. Neit, who wears the red crown of Lower Egypt, guards the dead, among other roles. Adorned with his two-feather crown, Amun-Re supports Egypt’s kings. Other deities employ features of felines and serpents to defend Re from malevolent forces that are always poised to attack. Re’s divine court also includes Hathor and Horus.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Creating the World

The creation of the world and its inhabitants is the subject of multiple ancient Egyptian myths, some of which are associated with specific local traditions and settlements. For those in Heliopolis (a site now within modern Cairo), the cosmos was formed by the deities of the Ennead. Slightly further south, in Memphis, Ptah was understood to have created the world and other gods through the act of speech.

Other deities are responsible for further feats of creation. They fashion humankind, facilitate the harvest, oversee the annual flood, and promote human virility and fertility. Substances such as semen, clay, and saliva give form to gods and humans alike in Egyptian myth. The deities who feature in these tales possess imagery as varied and distinctive as the materials and methods they use.

Despite their fundamental differences, the many accounts of creation were often presented as equally valid and complementary. This multiplicity of explanations demonstrates the complex nature of the belief systems. It illustrates how ancient Egyptian mythology was additive, combining manifold views on a single topic.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Coping with Life

Like people today, the ancient Egyptians had to cope with personal worries surrounding health, childbirth, competition, and love. Some deities took care of the world from state temples, where kings and priests attended their statues in restricted sacred spaces. But most people needed more tangible methods of reaching the gods to address personal problems.

All Egyptians could petition a powerful state god—for example, Amun-Re, Hathor, or Ptah—through public festivals. The deity left their temple hidden in a shrine on a barque, or boat, carried by priests. As the procession passed through town, members of the crowd could ask for a favor or blessing. Eventually, nonroyal people were given the opportunity to donate a statue, stela, or small figurine as a way to bring the individual closer to the divine presence. The offering could hold a request for attention, express gratitude, or represent a general sense of devotion.

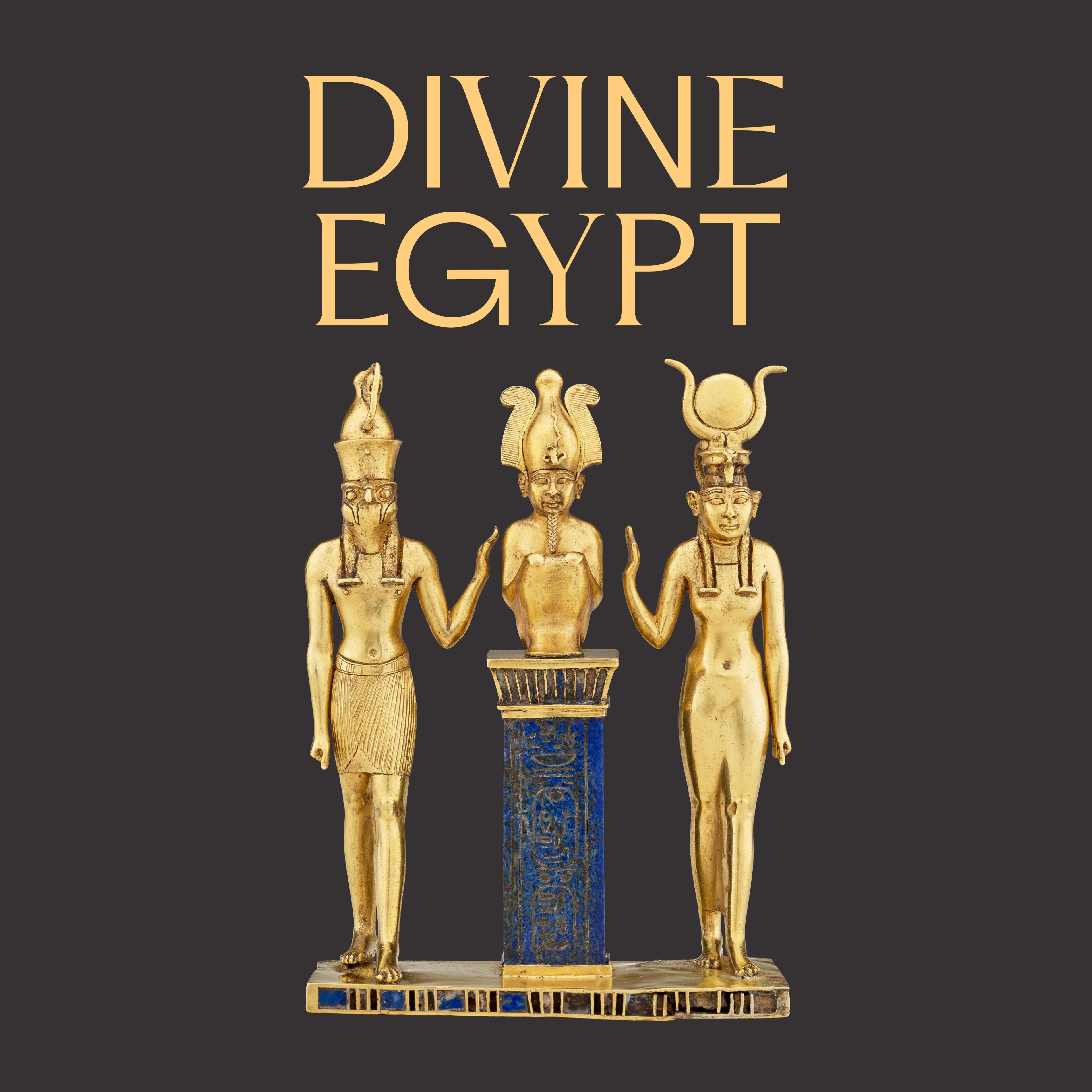

Some state deities, such as Isis with her son Horus, also came to be worshipped in publicly accessible shrines where people could ask for help. Hippo goddesses and Bes-images, hybrid deities that scared away negative forces, brought protection through their representations displayed in homes.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.

Overcoming Death

Tombs are some of the most significant monuments that survive from ancient Egypt. They reflect how critical it was for everyone, king and commoner alike, to achieve eternal life. The success of that dream is overseen by Osiris, a tall, shrouded deity who holds a scepter and flail and wears a distinctive crown. He rules the underworld and embodies the ideal of overcoming death.

Osiris’s most widespread image comes from the myth in which he is killed and dismembered by his brother, Seth. His sister-wife, Isis, and other sister, Nephthys, reassemble him, and ultimately Osiris is restored through funerary rites, with the help of Anubis. He recovers enough to father Horus and rule the realm of the dead.

The deities presented here embody the roles involved in a person’s funeral. Anubis embalms the deceased, Isis and Nephthys mourn, and Osiris is the prototypical mummified corpse. While the mythology of the underworld predominantly features these and a few other deities, hundreds of lesser divine beings, often called demons, also help or hinder the passage from this world to the next.

Selected Artworks

Press the down key to skip to the last item.